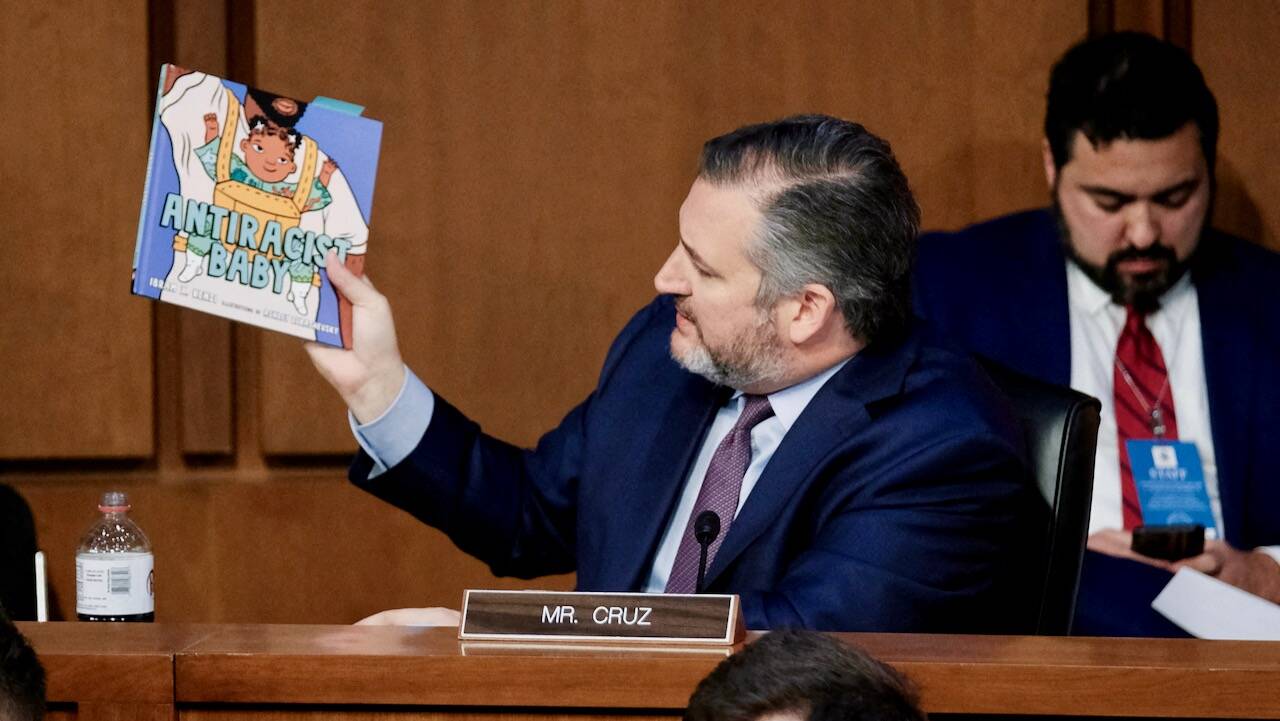

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.) holds up the children's book "Antiracist Baby," by Ibram X. Kendi, as he questions Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson on March 22 in Washington. (Michael Mccoy/Reuters) | Ted Cruz demonstrated this week that his wisdom as a senator is matched only by his discernment as a book reviewer. On Tuesday, the Texas Republican briefly hijacked the Supreme Court confirmation hearing of Ketanji Brown Jackson to quiz her about a couple of children's books. He was particularly worked up about "Antiracist Baby," written by Ibram X. Kendi, illustrated by Ashley Lukashevsky and unknown by Judge Jackson. Cruz struggled mightily to pin critical race theory on Jackson while an aide displayed large blowout images of "Antiracist Baby" as though they were frames from the Zapruder film. The leading auteur of White Outrage Theater, Cruz asked Jackson, "Do you agree with this book that is being taught to kids that babies are racist?" If the senator had managed to read all 24 pages of "Antiracist Baby," he would have seen the note to parents and caregivers at the end, where Kendi makes the perfectly reasonable argument that people are not born racist; they learn racist attitudes from the society around them — and far earlier than most of us want to admit. "It is our responsibility to counter those messages," Kendi writes, and not to feel so embarrassed about racism that we ignore it. What's more, he goes on to recommend that we "help children understand that racist policies are the problem, not people." But Cruz wasn't done misinterpreting kids books for polemic effect. He turned his attention to "Stamped (for Kids)," adapted by Sonja Cherry-Paul from the teen book "Stamped," by Kendi and Jason Reynolds. "On page 33," Cruz claimed, "it asks the question, Can we send White people back to Europe? That's what's being given to 8- and 9-year-olds." This is a gross mischaracterization of what "Stamped (for Kids)" actually says. The page that Cruz was referring to offers a discussion of Thomas Jefferson's conflicted attitudes about slavery. The authors rightly note that "one idea tossed around by White assimilationists was for Black people to 'go back' to Africa and the Caribbean." In a wry aside, the authors write, "Just imagine what Native Americans and Black people must have wished about their White oppressors: Can we send White people 'back' to Europe?" It's a passage infused with empathy, wit and historical insight. But those qualities were lost on Cruz as he charged ahead with his misrepresentation, twisting a crude comment hurled at Black Americans into an imaginary insult against White people. Naturally, Cruz's performance has caused sales of Kendi's books to soar. For her part, Jackson wouldn't be drawn into the senator's rusty old trap. All Americans should follow her example (my full rant). Novels continue to fuel an explosion of new movies and TV series. Adaptations of several popular books become available today: - Min Jin Lee's "Pachinko," one of the bestsellers of 2017 and 2018, debuts as a series on Apple TV+, starring Academy Award winner Yuh-Jung Youn, Lee Minho and Minha Kim. Earlier this month, director Kogonada told The Washington Post that he found the project overwhelming, revelatory and even scary (interview).

- A movie version of "Mothering Sunday," by Booker winner Graham Swift, opens in theaters. I thought the novella was elegant, if minor (review). But advance notices about the movie, starring Josh O'Connor and Odessa Young, have focused almost exclusively on the sex scenes. (Either the director has livened up the story, or I'm getting too old.)

- Speaking of nudity, "Bridgerton," based on Julia Quinn's Regency romance novels, returns to Netflix for season two. A recent interview in the U.K. revealed that the actors use a variety of props during their sex scenes, including "a deflated netball." (Now I'm thinking I'm not old enough.) Our TV critic, Inkoo Kang, says season two is "far less horny," but sports "a great deal more narrative polish and visual splendor" (review). The series has been a boon for Quinn's Bridgerton novels, which have sold more than 3 million copies in the U.S. Die-hard fans will also want to get her latest tie-in book, a compendium of quotations and character sketches called "The Wit and Wisdom of Bridgerton: Lady Whistledown's Official Guide." (How 'Bridgerton' flipped the racial script)

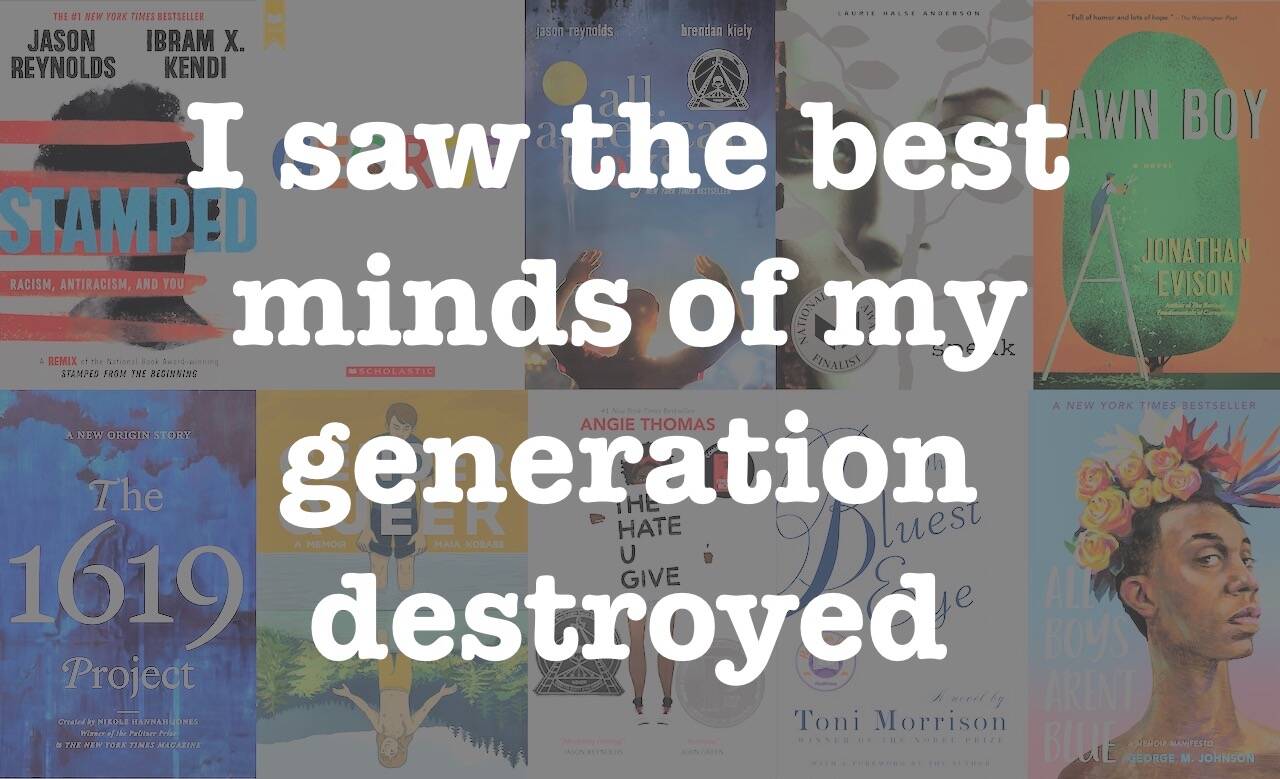

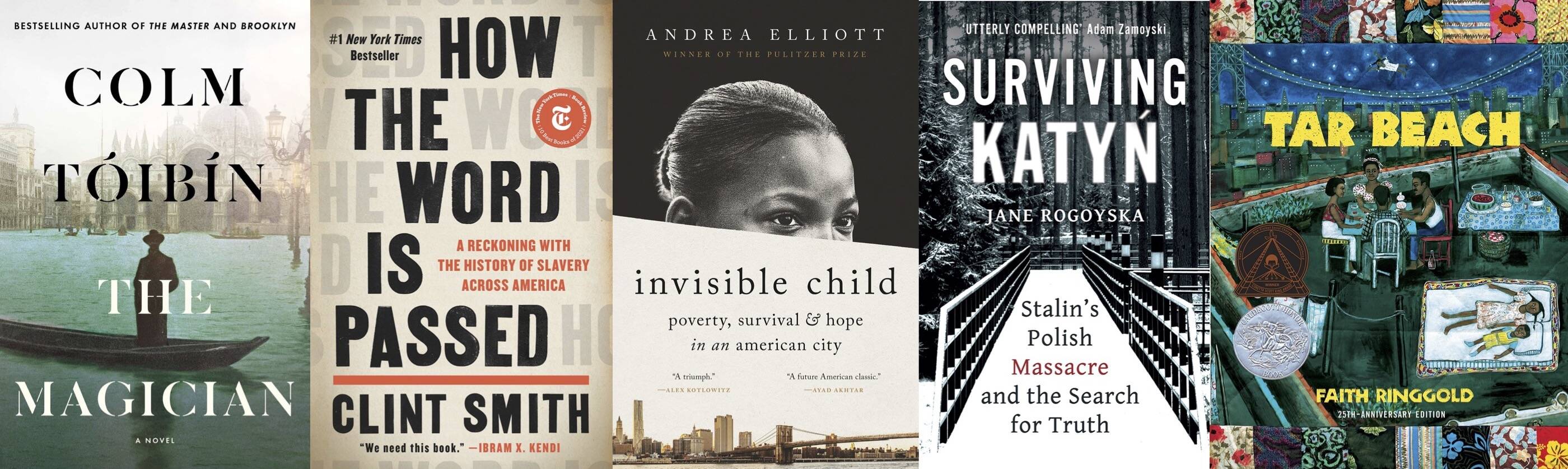

The opening of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" and a collection of recently banned books. (Photo illustration by Ron Charles/The Washington Post) | On this day in 1957, U.S. Customs seized 520 copies of Allen Ginsberg's "Howl and Other Poems." The books had been sent from England to San Francisco, where a customs official claimed, "The words and the sense of the writing is obscene. . . . You wouldn't want your children to come across it." Sometimes, it feels like we haven't made much progress over the last 65 years. Neo book-burners across America have been collecting dry sticks for months. Wannabe tyrants in Idaho came this close to passing their demonically titled House Bill 666, which would have sent librarians to jail for letting kids check out books that conservatives don't like. Librarians and teachers in other states are staring at similar bills. Throughout this alarming movement, I've been struck by how easy it is to destroy a good book. Again and again, sanctimonious protesters grab a few offensive words or phrases from a novel and wave them around at public meetings — like gangsters brandishing their enemies' severed hands to frighten the common folk into submission. It violates the literary and moral integrity of a work of literature to rip isolated parts out of context, and we all pay the price by sinking into the theocracy these activists impose. But the old tactics still work, which is why they're still being exploited. From Texas to Florida to the U.S. Senate, right-wing prigs have been howling about "pornography" in public schools and libraries. Countless beloved books, we're told, are full of material "you wouldn't want your children to come across." A dismaying story by Washington Post reporter Hannah Natanson notes that "school book bans are soaring." Several states have passed new laws banning vaguely defined offenses, usually involving references to sexuality or race. But even worse is the chilling effect: Administrators across the country are removing books from classes and libraries even before they're challenged, just to avoid any potential controversy (story). Sliding down this slippery slope, we've arrived at a tyranny-adjacent society: Fear of persecution is snuffing out more books than any of these new legal restrictions could ever hope to. Please get involved in your local school and public library. Make sure those administrators know you strongly support the rights of young people, students and adults to read what they want and need to. And remember: We're in the majority. A poll released yesterday by the American Library Association shows that 75 percent of Democrats and 70 percent of Republicans oppose efforts to remove books from public libraries (details). On the dedication page to "Howl," Ginsberg writes, "All these books are published in Heaven." So let us pray: "As in heaven, so on earth."  (Scribner; Little, Brown; Random House; Oneworld; Knopf Books for Young Readers) | This week's literary awards and honors: - Irish novelist Colm Tóibín won the Rathbones Folio Prize for "The Magician," his novel about Thomas Mann, which our reviewer called "incisive and witty" (rave). The award, worth about $40,000, is given to the year's best work of adult literature, in any genre and form, written in English and published in the U.K.

- Atlantic magazine writer Clint Smith won the Stowe Prize for "How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America," which our reviewer described as a "thought-provoking volume, with a clear message to separate nostalgic fantasy and false narratives from history" (review). The award is conferred by the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in Hartford, Conn., to honor a work of fiction or nonfiction that "illuminates a critical social justice issue in the tradition of Harriet Beecher Stowe's 'Uncle Tom's Cabin.'"

- "Invisible Child: Poverty, Survival & Hope in an American City," by Andrea Elliott, won the J. Anthony Lukas Book Prize (review). "Surviving Katyń: Stalin's Polish Massacre and the Search for Truth," by Jane Rogoyska, won the Mark Lynton History Prize. The awards, both worth $10,000, are conferred by the Columbia Journalism School and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard to honor the best American nonfiction books of the year.

- Artist and author Faith Ringgold received a lifetime achievement award from the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Mass. Now 91, Ringgold is the author and illustrator of many children's books, including the award-winning "Tar Beach" (1991).

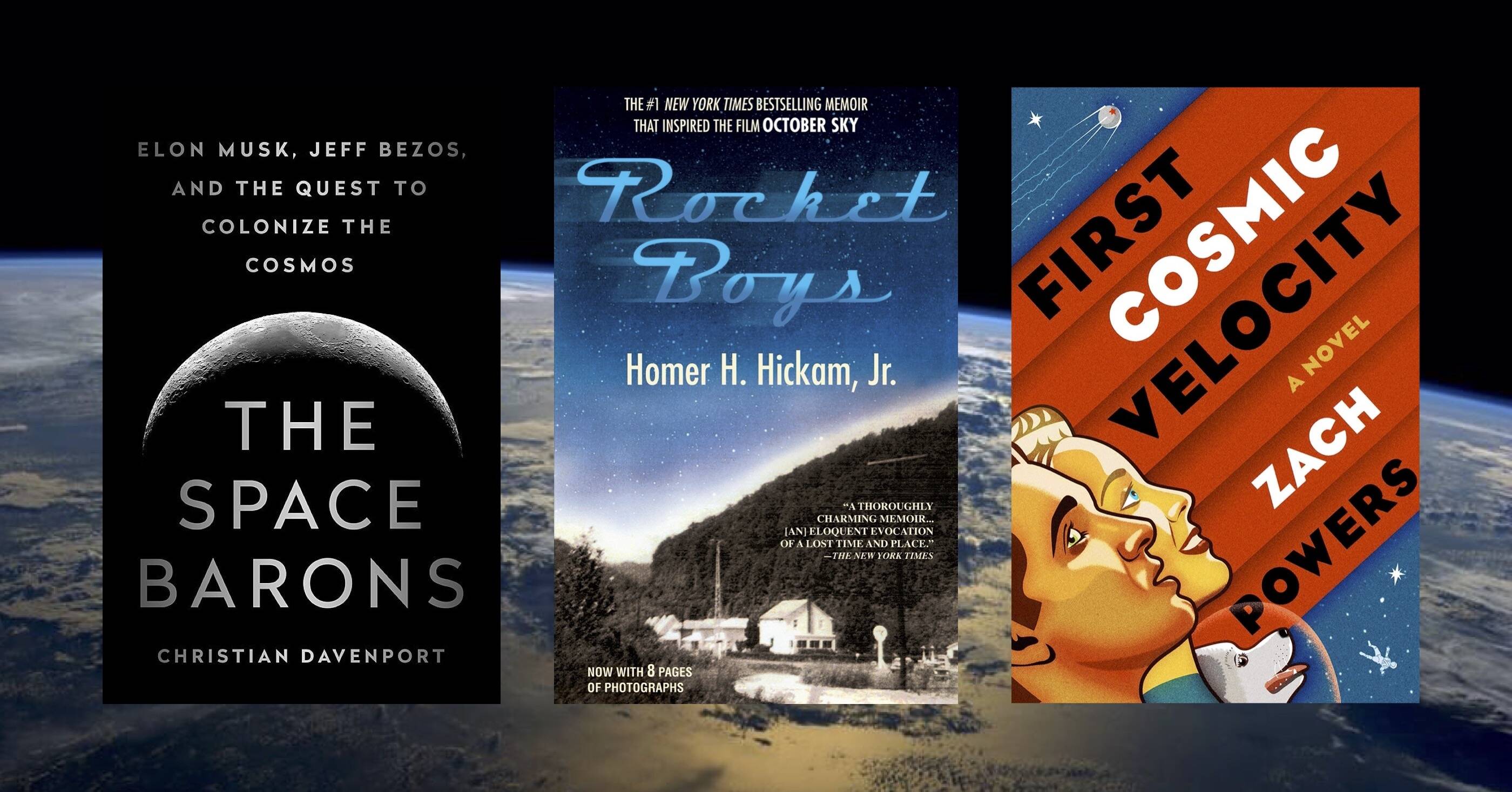

The SMART Copyright Act of 2022 would give the Library of Congress an expanded role in the fight against online piracy. (Aerial photo of the Library of Congress by Carol Highsmith/Library of Congress. Photo illustration by Ron Charles/The Washington Post) | A Republican and a Democrat are joining forces to curtail the ever-growing scourge of online piracy. Senators Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) and Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) have introduced the SMART Copyright Act. If passed, the legislation would mandate that online platforms establish and employ standard measures to identify and remove stolen recordings, videos and written material. "The technology exists to protect against this theft," Leahy said in a statement. "We just need online platforms to use the technology." The senator noted that Congress expected the industry to start using such methods decades ago, but it never did. Online theft is estimated to cost authors hundreds of millions of dollars per year. Violators are notoriously difficult to catch — particularly overseas —and online platforms bear little responsibility beyond removing stolen material when they're formally notified about it. For some authors, this "notice-and-takedown system" requires constant internet surveillance and a continuous submission of requests to remove content — all carried out with the discouraging knowledge that the situation is futile. The Strengthening Measures to Advance Rights Technologies (SMART) Copyright Act would authorize the Librarian of Congress to conduct a public discussion with stakeholders to establish industry-wide standards to combat online theft. The act would also establish new financial liabilities for online platforms. The Authors Guild supports the bill as a long overdue corrective to an intolerable problem for its members (details). But Re:Create, an advocacy group that includes the American Library Association claims that the SMART Act would "destroy online creativity, censor free expression online, hurt consumer choice and hold back new startups." Re:Create also warns that the filtering systems advocated by this legislation could "expose Americans to security and privacy threats." The Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties organization, calls the bill "an unmitigated disaster." As somebody whose livelihood depends upon rigorous copyright law, I'm inclined to believe the Authors Guild, but I'm ideologically sympathetic to radical free speech arguments, too. <sigh> This is one of those very technical, boring things that could actually make a huge difference — for good or ill — in our lives. Stay tuned.  (PublicAffairs; Delacorte; G.P. Putnam's Sons; background photo credit: NASA/Reid Wiseman) | So much on Earth is being destroyed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine that it may seem irrelevant to consider the ramifications in outer space. But scientists, diplomats and politicians are struggling to figure out if it's possible to continue doing research with a nation accused of actively committing war crimes. It doesn't help that Dmitry Rogozin, director general of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, is an enthusiastic supporter of the invasion. On his shockingly immature Twitter feed, Rogozin has suggested that the International Space Station could fall on the U.S., Europe, China or India. "It is unclear how the countries will continue to work together in space, as tensions between the Cold War adversaries mount on the ground," wrote Washington Post reporter Christian Davenport. He's also the author of "The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos" (review). (Bezos owns The Washington Post.) Homer Hickam says our relationship with Roscosmos is already ruined beyond repair. He's a former NASA engineer and the author of several best-selling memoirs, including "Rocket Boys," which inspired the film "October Sky." In a recent op-ed in The Washington Post, Hickam wrote, "It's time to end our well-intentioned partnership with Russia — even if, as seems almost certain, it would mean the early closing and decommissioning of the space station" (essay). All this sad news inspired me to start reading Zach Powers's "First Cosmic Velocity" (2019). It's a historical novel about the Soviet space program in the 1960s. In Powers's telling, the Soviets can get their cosmonauts into space, but they don't have the technical expertise to get them home. To satisfy Khrushchev and serve the empire's propaganda needs, the agency secretly uses twins as cosmonauts: When one burns up during reentry, the twin does the victory tour. "First Cosmic Velocity" is a quirky, melancholy story that explores the human costs of obsessive national secrecy and terrifying political corruption. What makes it even more strikingly relevant are alternate chapters set in 1950 in Ukraine where a future cosmonaut and his twin brother are growing up under the heel of Russian domination. No wonder today's Ukrainians were ready.  (Courtesy of "Selected Shorts") | Fiction lovers: Tune in tomorrow for 12 hours of "Wall to Wall Selected Shorts." It's an all-day celebration of the 35th anniversary of the public radio show "Selected Shorts." During the live-streamed program, you'll hear stories by Aimee Bender, Michael Cunningham, Edwidge Danticat, Dave Eggers, Lauren Groff, Victor LaValle, Elizabeth Strout, Luis Alberto Urrea and many more performed by professional actors such as Hugh Dancy, Cynthia Nixon, Amber Tamblyn, Liev Schreiber and more (register for free here). If you're in New York, you can drop by Symphony Space between 11 a.m. and 11 p.m. and enjoy the story performances in person. For a donation of $75 or more, you can get a reserved seat (more information). All the stories in tomorrow's program are available in a new anthology called "Small Odysseys," edited by Hannah Tinti. In his foreword, Neil Gaiman describes falling in love with radio stories as a boy. "Selected Shorts" has been keeping that magic alive for decades. "Stories are the way we interact, the place that groups come together," Gaiman writes. "We look out through other eyes, imagine ourselves in other skins, experience lives we wished we could lead or are relieved we never will."  Wesleyan University Press | Rae Armantrout, who has won a National Book Critics Circle Award and a Pulitzer Prize, writes sly poems that move so fast it's easy to miss their deadly serious profundity. In the 1970s, she was associated with a group called "the Language poets," possibly literature's most baffling appellation. Armantrout is not entirely satisfied with that group label either, but when I spoke with her for Life of a Poet in 2017, she explained that the Language poets were "dealing with the fact of what happened to language during the Vietnam War: the spirit, the spin, the having to destroy a village in order to save it" (video interview). Her new collection, "Finalists," which contains more than 100 poems, brings that inquisitive linguistic spirit to our modern era with similarly unsettling effect. Transfer For Mark Kruse Now they tell us

"orbit" is wrong. Electrons don't actually

"orbit a nucleus." Perhaps they are looking for the word

"haunt." One meaning of haunt

is to frequent. To be known

to appear. They say electrons leap

from nonexistent

rung to rung, giving off energy as a ghost may vanish

from one room

to materialize in the next, causing the audience

to jump. From "Finalists," by Rae Armantrout (Wesleyan University Press, 2022). Used by permission of the publisher and author.  Ron and Dawn Charles at Planet Word, a newish museum in Washington, D.C., on March 19, 2022. (Ron Charles/The Washington Post) | Even if you can't make it to Washington in time to catch the cherry blossoms, the capital has plenty to offer — like Planet Word. This $60 million museum opened during the height of the pandemic, so I wasn't able to see it till last Saturday. I'd been deeply skeptical: A museum about language — isn't that what we call "a library"? But no, Planet Word is a dazzling playground for the linguist in us all (review). On three floors of the cleverly remodeled Franklin School (catty corner to my office), Planet Word offers a small number of brilliantly conceived exhibits. In one airy room dominated by a glowing globe, visitors experience the remarkable qualities of languages from around the world. In another room, a spiral strip of computer monitors explores the way advertisers manipulate language. And there is a library, too, but it's a magical one. This weekend a new exhibit opens called "Lexicon Lane." Designed to look like an old village, it's a "word-sleuthing adventure" that challenges visitors with 26 puzzles. Admission is free, but Dawn and I managed to spend $85 in the gift store on bookish puzzles, socks, jewelry and greeting cards. It could have been worse: We were seriously eyeing a set of grammar-advice dishes to lay (lie?) on our kitchen table. One more thing: The Washington Post is looking to hire an Assistant Nonfiction Books Editor. This is a new position for us, and we're speechless with optimism about the future (more information). Meanwhile, send any questions or comments about our book coverage to ron.charles@washpost.com. You can read last week's issue here. Why not forward this newsletter to friends who might enjoy it? Anyone can sign up for free by clicking here. (You don't have to be a Washington Post subscriber.)

Interested in advertising in our bookish newsletter? Contact Michael King at michael.king@washpost.com. |