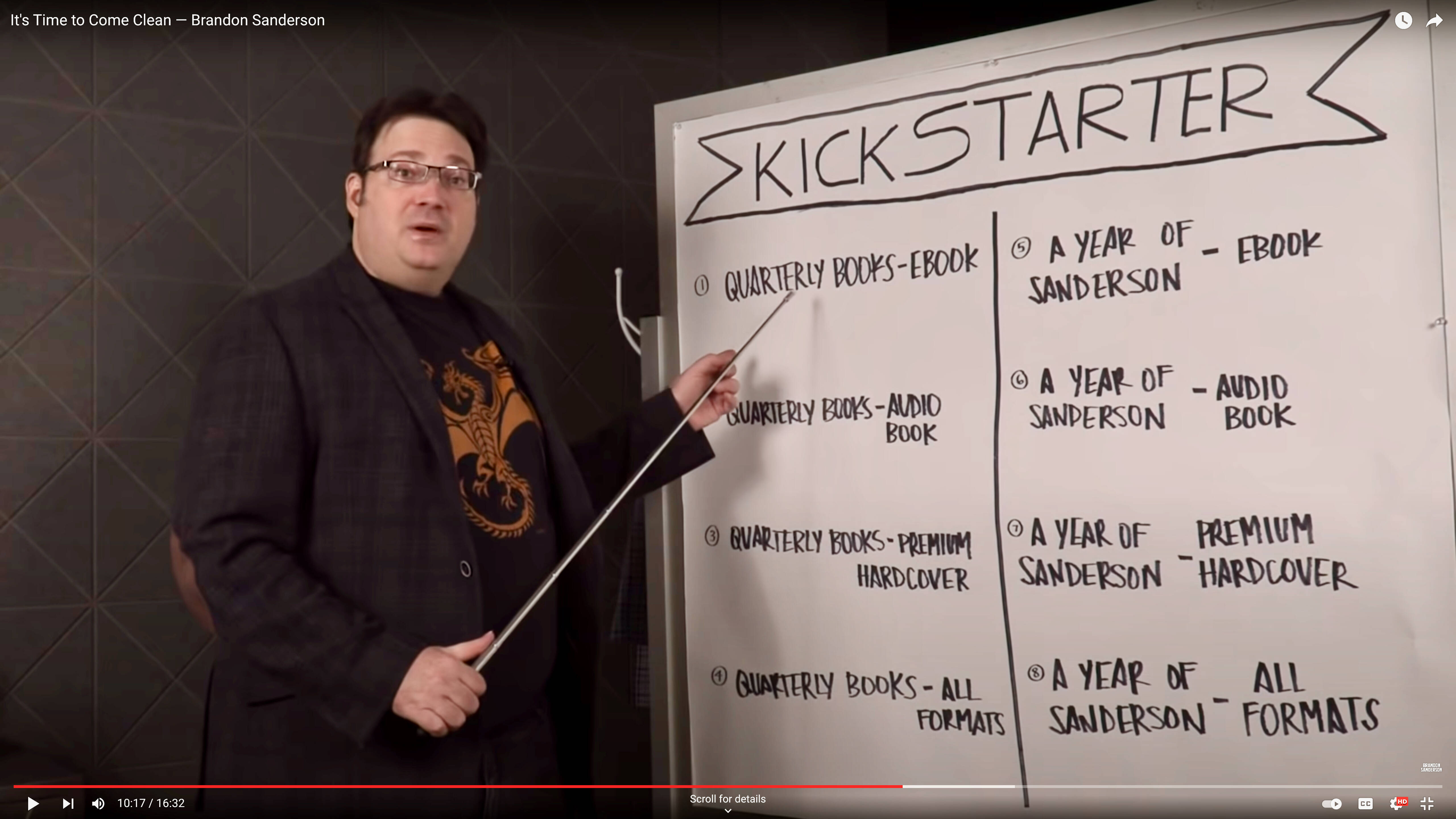

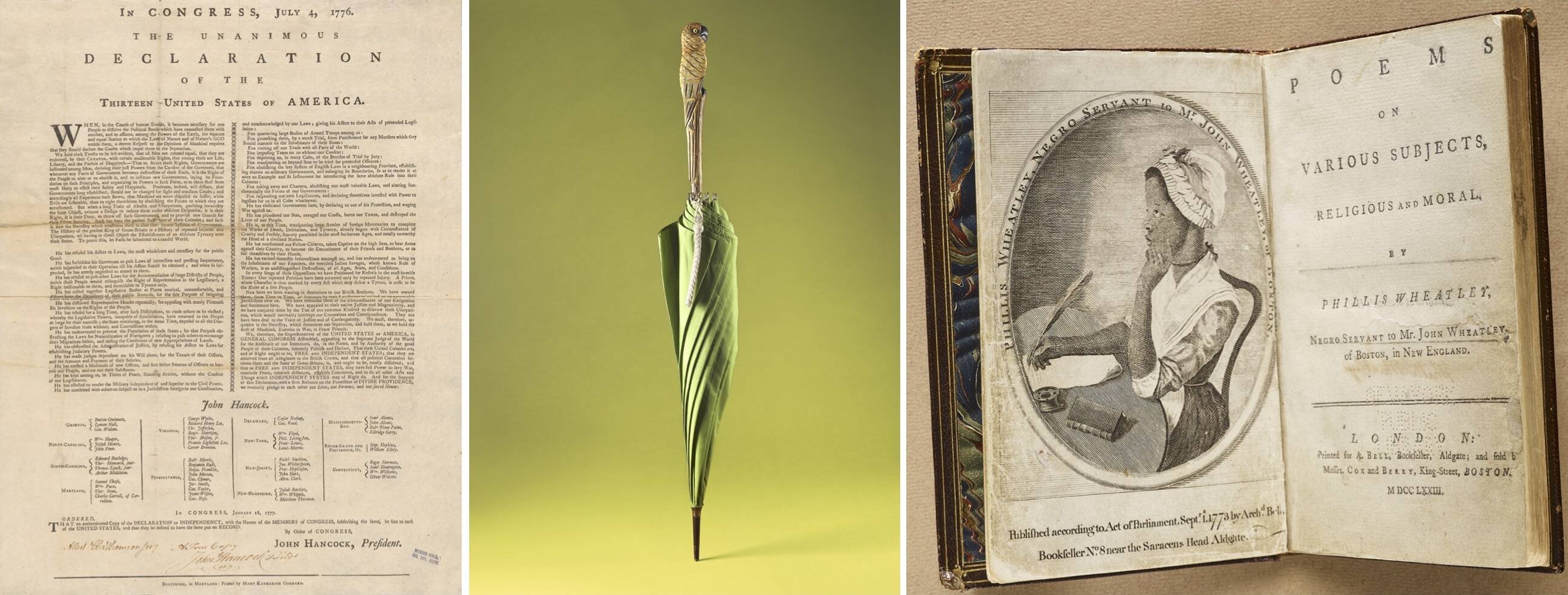

Volunteers make camouflage nets for the Ukrainian military at a library in Lviv, Ukraine on March 1, 2022. (Photo by Yuriy Dyachyshyn /AFP via Getty Images) | The Ukrainian Library Association was supposed to be holding a conference this week, but something came up. A note on the association's Facebook page explains, "The insidious, brutal and bloody aggression of the Russian Federation prevented us from realizing our plans." But these are librarians we're talking about, so they're not discouraged: "The organizing committee has decided to hold the conference after our confident victory." Meanwhile, registration fees collected for the conference have been sent to support the Ukrainian army. Nicholas Poole, the CEO of Britain's library and information association CILIP, has been in contact with Yaroslava Soshynska, director of the Ukrainian Library Association. He tells me, "Her last request to me was to do everything we can to draw the world's attention to Ukraine's culture, identity, history and its right to exist as a sovereign people. I think their greatest fear, other than for their own safety and that of their families, is of erasure as a culture." Tragically, that fear is justified. In "The Library: A Fragile History," Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen write, "Libraries had always been a target of conquering armies." Although Russia is a signatory of the 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, Vladimir Putin's bombing of civilian targets in Ukraine aligns with his claim that it's not a real country. As a former KGB agent, he's just following the empire's old playbook. In "Libricide: The Regime-Sponsored Destruction of Books and Libraries in the Twentieth Century," Rebecca Knuth observes, "The Soviet Union, in the interest of extinguishing national identity among its constituent nations, was guilty of some of the most egregious cultural destruction." In 1940, the last time the world was at war, Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish wrote, "Keepers of books, keepers of print and paper on the shelves, librarians are keepers also of the records of the human spirit." In language that now sounds like the rallying cry of Ukrainian librarians, MacLeish went on to say, "When wars are made against the spirit and its works, the keeping of these records is itself a kind of warfare. The keepers, whether they so wish or not, cannot be neutral." On Wednesday, the Ukrainian Library Association laid the groundwork for a National Digital Library of Ukraine. "Let the first collections be collections of this war and our victory!" the group announced on its Facebook page. "No librarians are sitting with their hands folded today!" They admonished people to begin collecting documents, photos, videos, recordings, posters, anecdotes, jokes — anything to "demonstrate our innocence, our righteous rage and our unbeatable humor."  Brandon Sanderson launched "A Year of Sanderson" Kickstarter on March 1, 2022. (Youtube screenshot) | Brandon Sanderson is a popular writer of epic fantasies, but nothing he's written is so epic and fantastical as what happened to him this week. On Tuesday, Sanderson launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise $1 million to sell four novels that he wrote secretly during the covid pandemic. By midnight, he'd raised $13.5 million. This morning — just four days into his month-long campaign — more than 83,000 readers have pledged more than $20 million. This is the kind of magic we're used to seeing in the make-believe world of cryptocurrencies, not in the parsimonious halls of publishing. "It's been just an incredible ride," Sanderson told me last night from his home in Utah. On Kickstarter, fans can sign up for a variety of packages to receive his four novels, one per quarter, in 2023. The offers start at $40 for the e-books and reach all the way to $500 for a bundle of e-books, audiobooks, hardbacks and monthly swag boxes designed, Sanderson says, "for the fans as crazy as I am." He explains these options in a wildly verbose, self-satirized video complete with multiple whiteboards (watch). But surely nobody is laughing in New York. Sanderson's astonishing success poses an existential challenge to the entire book industry: If the most popular authors can reach their readers directly, what's to keep them from bypassing agents, editors, publishers, distributors and retailers? Such authors wouldn't even need Amazon. Sanderson insists that he appreciates and will continue working with Tor, his publisher. And besides, very few successful authors want to manage the complicated and expensive mechanics of publishing their own books. Sanderson has warehouses. He employs a staff of 30 people – so many that he needs an H.R. director. His author friends tell him, "We became writers so that we didn't have to do that." But Sanderson wanted to launch this Kickstarter to demonstrate to New York publishers that they need to be more responsive to readers' desires for bundling multiple formats and selling related book merchandise. "I've been talking to New York about this for years," he says. "Ours is the only industry I can think of that doesn't try to upsell when you have such a dedicated fan base. It's just baffling to me that we aren't providing the things that people want." I detect a bit of a prepper mentality, too. Part of Sanderson's motivation for this campaign is to make sure that he and his team can print hundreds of thousands of books and ship them on their own "just in case something happens." He's also concerned about Amazon's dominance and the online retailer's rising advertising fees. "I want to know that if for some reason Jeff Bezos decided he hated me and pushed a button . . . I have another recourse." He recalls that during a pricing dispute in 2010, Amazon pulled Macmillan's books from its website for about a week. If that happens again, he'll be ready. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.) "I have a very artistic temperament," Sanderson says, "but I was trained by an accountant, my mother, and she's a really good accountant." No magic in the Cosmere is as powerful as that.  Novelist Meg Wolitzer is the new permanent host of "Selected Shorts," produced live at Symphony Space in New York, broadcast weekly on public radio and streamed as a podcast. (Photo courtesy of Symphony Space) | "Tell me a story." That's been the imperative behind "Selected Shorts" since the show launched in 1985. Each episode features well-known actors reading short works before a live audience. It's great literature brought to your ears by the world's most engaging voices. Meg Wolitzer is the new permanent host of the public radio program and podcast version of "Selected Shorts." For the acclaimed writer of such novels as "The Wife," "The Interestings" and "The Female Persuasion," it's a dream gig. "When they asked me if I would be interested in doing this, I was so thrilled because, first of all, I get to have more short stories in my life, which is always a good thing," Wolitzer says. For the last 10 years, "Selected Shorts" has employed a rotating cast of guest hosts for each episode; Wolitzer's appointment marks a new beginning for the show. Her first episode, titled "Complicated Women," debuted yesterday, and it's terrific. It includes the late Lynne Thigpen performing an essay by Edwidge Danticat, Joanna Gleason performing a story by Claire Luchette, and Joan Allen performing a hilarious excerpt from Nora Ephron's autobiographical novel "Heartburn" (listen here). "Being open to stories, to what another person thinks, is just what reading fiction does so beautifully," Wolitzer says. "And the listening form, in particular, allows you to be — with your headphones on — surrounded by the sensibility of the writer." "Selected Shorts" adds an element of performance that's captivating. "I'm fascinated by the different ways that a writer might get into a character and an actor might get into a character," she says. "They have different qualities. I'm amazed at how actors slow down and just let the story marinate." Disclosure: Meg and I are old friends. Years ago, we tried to start our own books podcast, an antidote to the somnolent literary chats that ruled the web. Nothing ever came of our efforts, except many hilarious hours together, including one surreal afternoon with Fran Lebowitz in a New York apartment filled with hundreds of antique bobbleheads.  "Treasures: Trailblazing Women Through History": The Declaration of Independence, printed in Baltimore by Mary Katharine Goddard in 1777; an umbrella belonging to P.L. Travers, the author of "Mary Poppins"; "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral," by Phillis Wheatley, published in London in 1773 (Photos courtesy of the New York Public Library) | In the late 18th century, 13 colonies under the yoke of a despot dared to declare their independence. No women were allowed to join the deliberations on that treasonous document. But a woman named Mary Katharine Goddard published the first copy of "The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America" that included a list of most of the signers' names. The Goddard Broadside, as it's now known, is a highlight of "Treasures: Trailblazing Women Through History," an online guide designed by the New York Public Library to celebrate Women's History Month. The exhibit demonstrates "the barriers women have broken and spaces they have made for themselves in the arts, sciences, literature, politics, and more through innovation, creativity, and advocacy." Among the treasures, drawn from the ongoing Polonsky Exhibition at the main library, are Mary Wollstonecraft's manuscript of "A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" and Maya Angelou's handwritten draft of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings." There are also curious objects such as Charlotte Brontë's writing desk and Virginia Woolf's walking stick, which I'm assuming walks off in all directions at once. You can view the exhibit online here or see these rare documents, books and objects in person at the main New York public library. (It's free, but you must have a timed ticket.)  "Putin's Russia: The Rise of a Dictator," by Darryl Cunningham (Drawn and Quarterly); background photo shows a building burning after being shelled in Kyiv, Ukraine, on March 3, 2022. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky) | Darryl Cunningham's timing is dangerously good. He's just published a graphic novel about the life and crimes of the world's most reviled living leader. "Putin's Russia: The Rise of a Dictator" begins with brief stories about a small boy who grew up poor and took "vengeance on anyone who attempted to humiliate him." From there, Cunningham carries readers through Russia's complex modern history of reform and corruption with bold blocky illustrations and straightforward explanations. In well-drawn asides, he laments Obama's weak response to the annexation of Crimea and explores Trump's "ceaseless fealty" to the foreign leader who sought to subvert the U.S. presidential election. But Cunningham's book is most effective in dramatizing the poisonings, bombings, heart attacks and shootings that Putin's critics have suffered as his dark star has risen. Some of these horrors will be familiar to anyone who's been paying attention, but having them all laid out here in black and white and pools of red is tremendously powerful. Cunningham, who lives in England, tells me it's been "kind of alarming" to see his predictions about Putin play out over the past few weeks (the latest news). He upbraids Western leaders for missing Putin's transformation from a bureaucrat into "a megalomaniacal dictator." And in the final pages of his book, he writes that "Putin and his cronies are deserving of the most crushing sanctions and political isolation." The author-illustrator has been encouraged to see that advice become reality, but he cautions that Western nations must still do more: They should stop relying on Russian oil and gas, and they must stop allowing members of the Russian kleptocracy to store their billions in glitzy real estate and legitimate banks. For people (like me) unused to the graphic novel format, it's strange to cover such consequential real-life material this way. "That's one of the beauties of the comic medium," Cunningham says in his soft, lilting voice. "You can take a lot of information and then boil it down. And if you're good at it, you can show it in a clear and concise manner." Cunningham is very good at it. "Putin's Russia" is illuminating and chilling.  Amazon Books in Bethesda, Md., is one of about two dozen bookstores that will be closed, according to the online retailer. (Dawn Charles/The Washington Post) | In 2015, Amazon started opening physical bookstores. They were sleek and efficient, an algorithm's answer to the question, "Alexa, what is literary culture?" But after Amazon had already captured an enormous segment of the book market online, there was something unseemly about competing against imperiled indie bookstores, like hunting in an animal hospital. Lo and behold: Amazon announced this week that its physical bookstores will be shuttered (story). That marks a reprieve for indie bookstores; grocery stores aren't so lucky. An Amazon spokesperson said, "We've decided to close our Amazon 4-star, Books, and Pop Up stores, and focus more on our Amazon Fresh, Whole Foods Market, Amazon Go, and Amazon Style stores." The company will continue to perfect its "Just Walk Out" technology, which allows customers to select items and leave the store without waiting in checkout lines. The spokesperson added, "We remain committed to building great, long-term physical retail experiences and technologies, and we're working closely with our affected employees to help them find new roles within Amazon." Barnes & Noble CEO James Daunt responded to Amazon's news with his usual British poise. "The closure of a bookshop is always regrettable," he told me. "We have far too few." Then he added, "Some might say there is an exception to every rule." The impact of Amazon's physical bookstores — two dozen around the country — always remained relatively small. But Allison Hill, CEO of the American Booksellers Association, told me, "Amazon's closures will have a positive direct sales impact on independent bookstores that are near Amazon stores. And it will ensure that a neighborhood's local bookstore is once again a community bookstore. There's also a beneficial ripple effect for all independent bookstores when Amazon takes a step back from the book business." The ABA is currently advocating passage of legislation designed to thwart Big Tech. For instance, the Twenty-First Century Antitrust Act being considered in New York State would prohibit "abuse of dominance" — a more aggressive legal standard than current federal antitrust regulations. With a few exceptions, the New York law would punish any business that controls 40 percent of the market as a seller or 30 percent as a buyer. Violators could be jailed.  Russian President Vladimir Putin addresses the nation in the Kremlin on Feb. 21, 2022. (Library of America; Alexei Nikolsky, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP; Blue Rider) | I felt a queasy sense of déjà vu this week when Vladimir Putin announced that he'd moved Russia's nuclear arms to "high combat alert" (story). In college, I read a terrifying series of essays in the New Yorker by Jonathan Schell about the effects of nuclear war. I still have a visceral memory of sitting in the dining hall transfixed by Schell's description of how multiple blasts would incinerate the planet in a matter of hours. I was loads of fun in college. By grim coincidence, this year marks the 40th anniversary of those essays, which Schell published as a book called "The Fate of the Earth." Today, it's impossible to imagine such a grim little tome having the impact that "The Fate of the Earth" had in 1982. It was hailed (or condemned) everywhere by everyone. In a withering takedown in Harper's, Michael Kinsley called it "huge and exotic blossoms of ratiocination that could grow only in an environment protected from the slightest chill of common sense." He said Schell's "moral solemnity is a form of blackmail." But such criticism did little to blunt the book's influence. The disarmament movement, already agitated by Ronald Reagan, was energized by Schell's foreboding argument, and "The Fate of the Earth" ignited an explosion of books on nuclear war. Although Schell has gone beyond the reach of nuclear annihilation (obituary), the half-life of his most famous book has been long. Washington Post writer Dan Zak was born just a year after "The Fate of the Earth" appeared, but in 2016 he published "Almighty: Courage, Resistance, and Existential Peril in the Nuclear Age" (review). Written in the shadow of Schell's apocalyptic vision, it's a fascinating study of our atomic predicament that focuses on three peace activists who easily breached a Tennessee nuclear weapons facility. Were they heroes or crazies? More than 10,000 nuclear bombs still exist — enough to destroy all life on Earth many times over — but most of us don't talk much anymore about nuclear war or nuclear disarmament. "The Fate of the Earth" now appears in a volume published by Library of America, as though it were a cherished literary relic like the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. It's not that we learned to stop worrying and love the bomb; it's that we've learned to forget it. And that is certainly worse.  University Press of Kentucky | Crystal Wilkinson, the poet laureate of Kentucky, won the 2022 NAACP Image Poetry Prize for her debut collection, "Perfect Black." These are powerful, searching works of poetry and prose, evocatively illustrated by Ronald W. Davis. "Wilkinson teaches us in 'Perfect Black' that the black body of the world has seen and heard and felt more than its share of lamentation and longing," Nikky Finney writes in her foreword. "In the end, which never arrives in this collection, we finally understand this is how the circle is made — how black is made perfect and is never ever for the faint of heart." The Water Witch on Salvation When the horses took off with the wagon

& my grandbaby inside, i chased it.

My legs nigh on seventy, moved like a lightning twenty—

down the bank & across the pasture,

I hollered out, Hah up now!

& old Trigger stopped,

stood stiff & straight, real proud,

cutting his black eyes at me like he was saying

You old sumbitch, i showed you.

I lifted the baby out, rested her on the ground—safe.

The baby took my finger; she didn't cry a lick.

We left the wagon, walked the horse back to the barn,

then that girl breaks my grip & runs; she runs, she runs

through the pasture, up the hill, as if nothing happened at all.

Not a tear one, nare one sign of being scared.

The nip in the morning made me think of old hog killing times,

made me think of Old Man Pat,

who'd rather see the fresh chitlins rot on the ground

than me take em home to feed my younguns.

I felt old Trigger's breath on my hand, warm & stank.

I pat his flank & we're back to being friends.

The hurtin in my knee comes back on me like a toothache,

made me wonder if any living thing could ever be tamed. Excerpted from "Perfect Black," by Crystal Wilkinson (The University Press of Kentucky). Copyright © 2021 by the University Press of Kentucky. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.  The survivors of my book reviewing workshop atop the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington on Feb. 26, 2022. (Shaquetta Nelson/Day Eight) | Last Saturday was a big day for me. I went to the MLK public library – my first time since it reopened – and taught a workshop on book reviewing for an arts organization called Day Eight. (America's libraries are essential now — and this beautifully renovated one in Washington gives us hope.) The students, all adults, were smart and curious. Three of them submitted their own book reviews for us to critique as a group. After almost two years of working at home, I was downright giddy. It was an inspiring, desperately needed reminder that normal life is just around the corner. Hang on! Meanwhile, if you have any questions or comments about our book coverage, write to ron.charles@washpost.com. You can read last week's issue here. If your friends would enjoy this free newsletter, please forward it to them and tell them they can subscribe by clicking here.

Interested in advertising in our bookish newsletter? Contact Michael King at michael.king@washpost.com. |