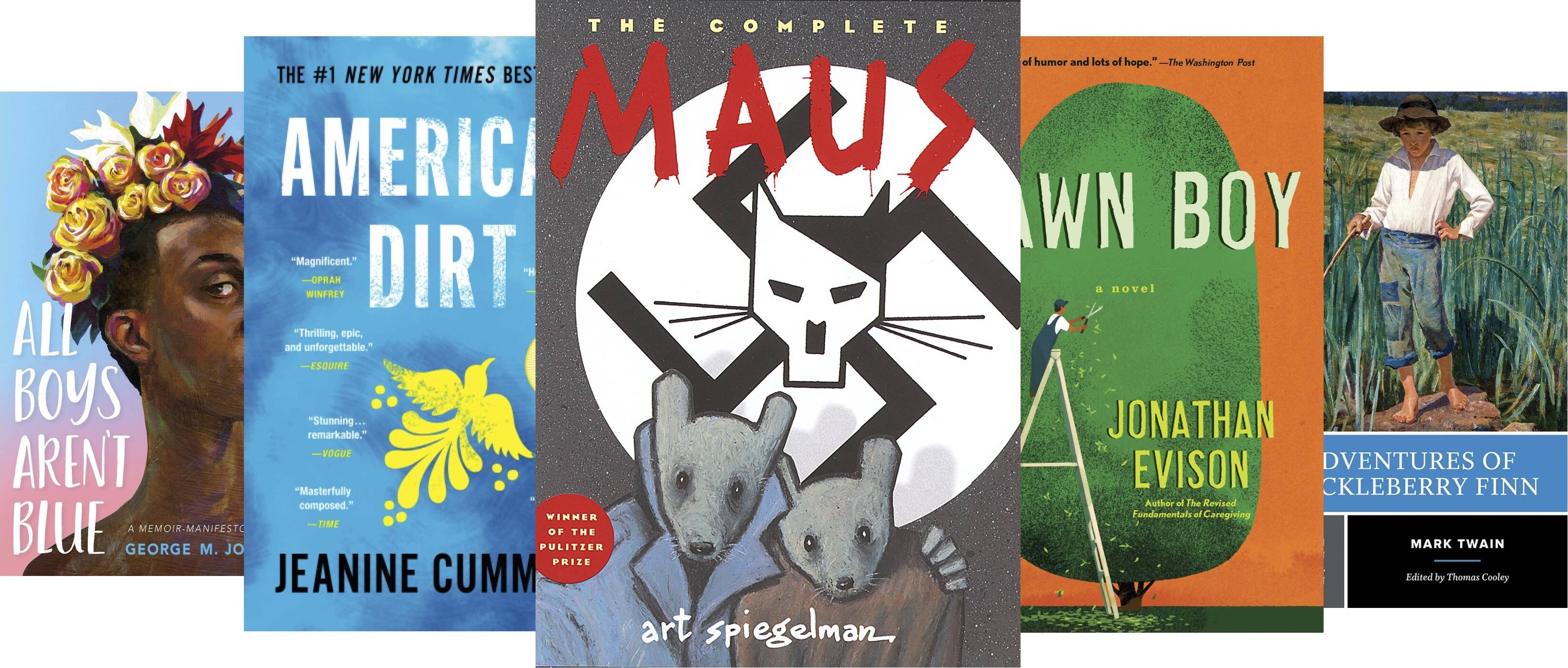

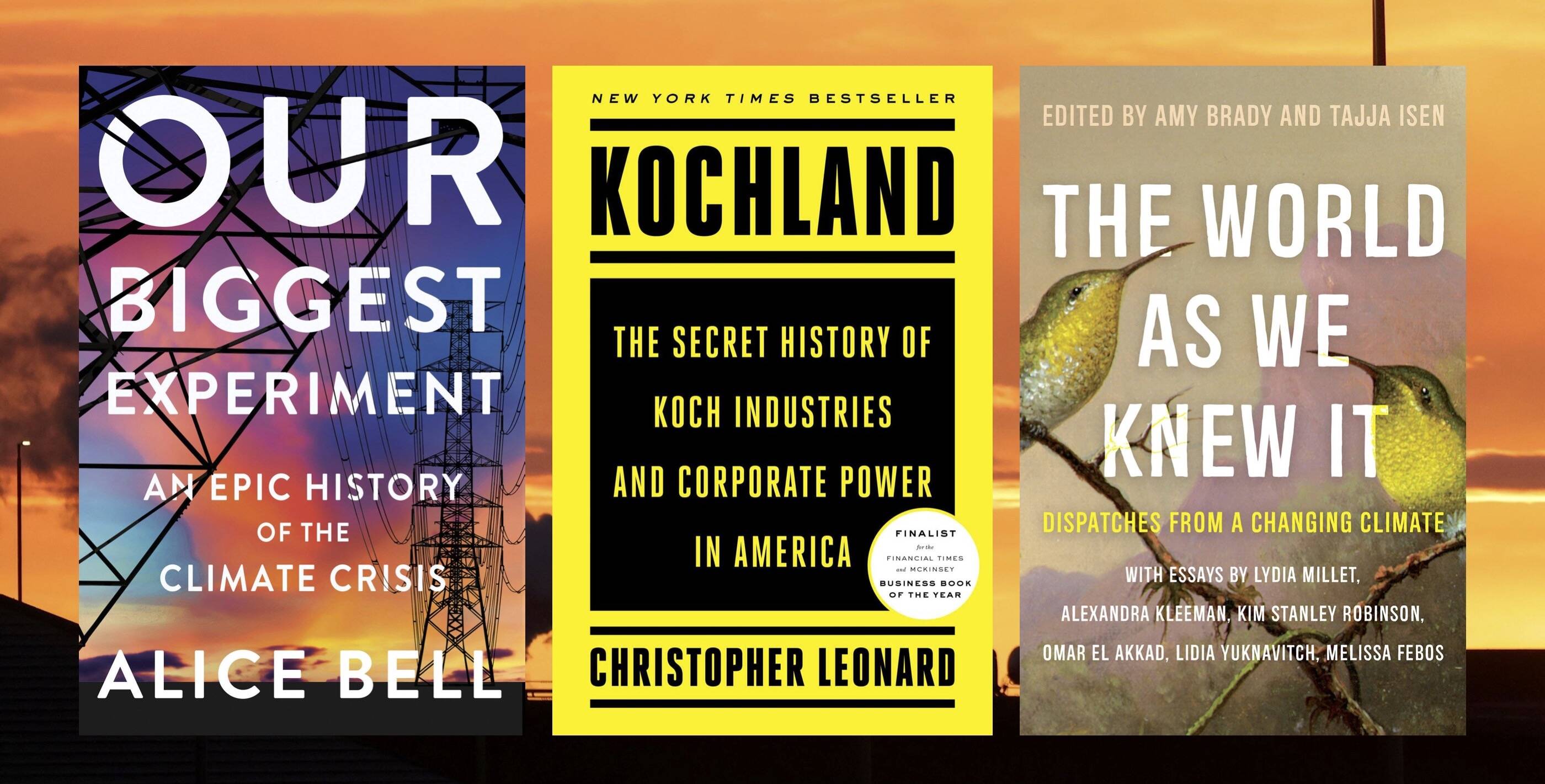

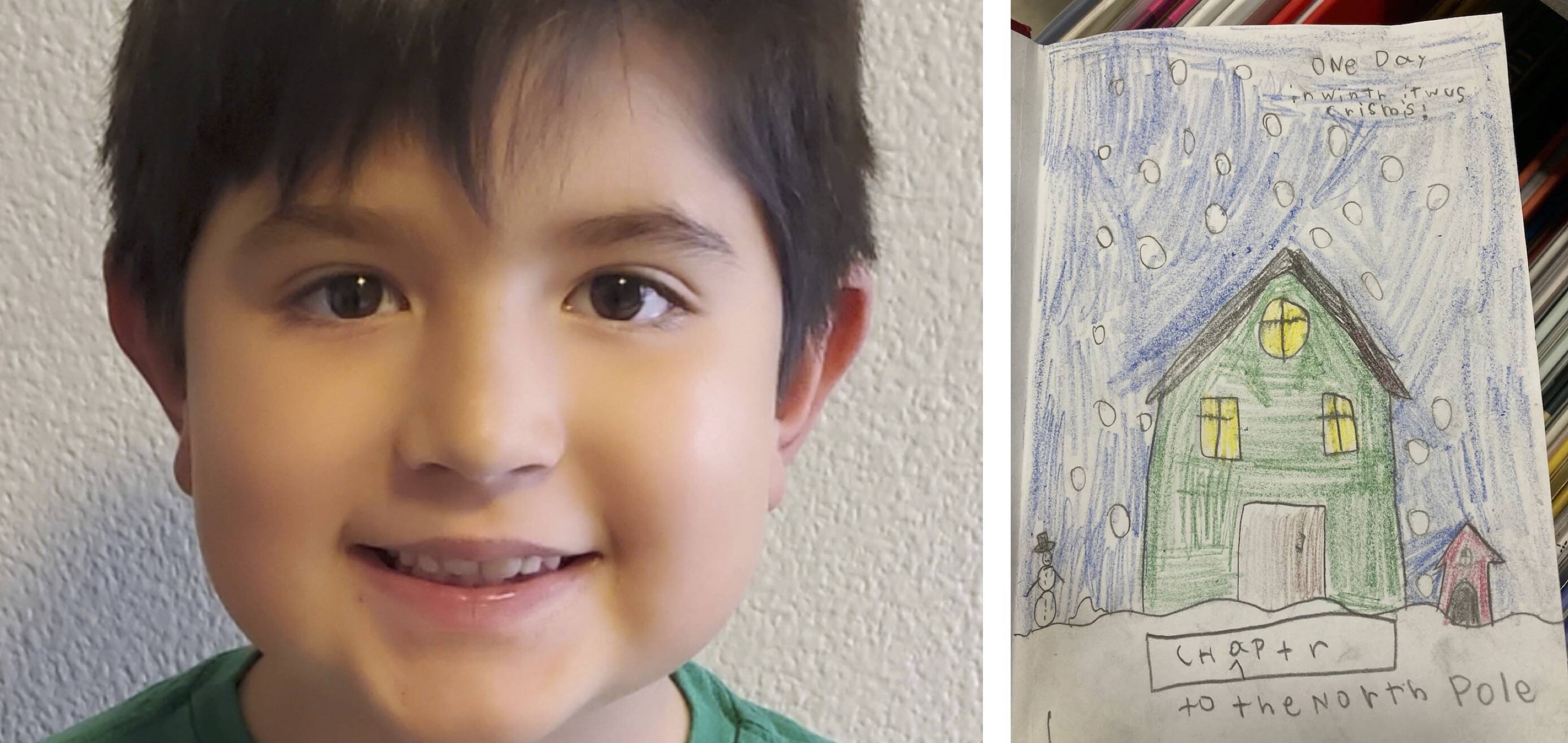

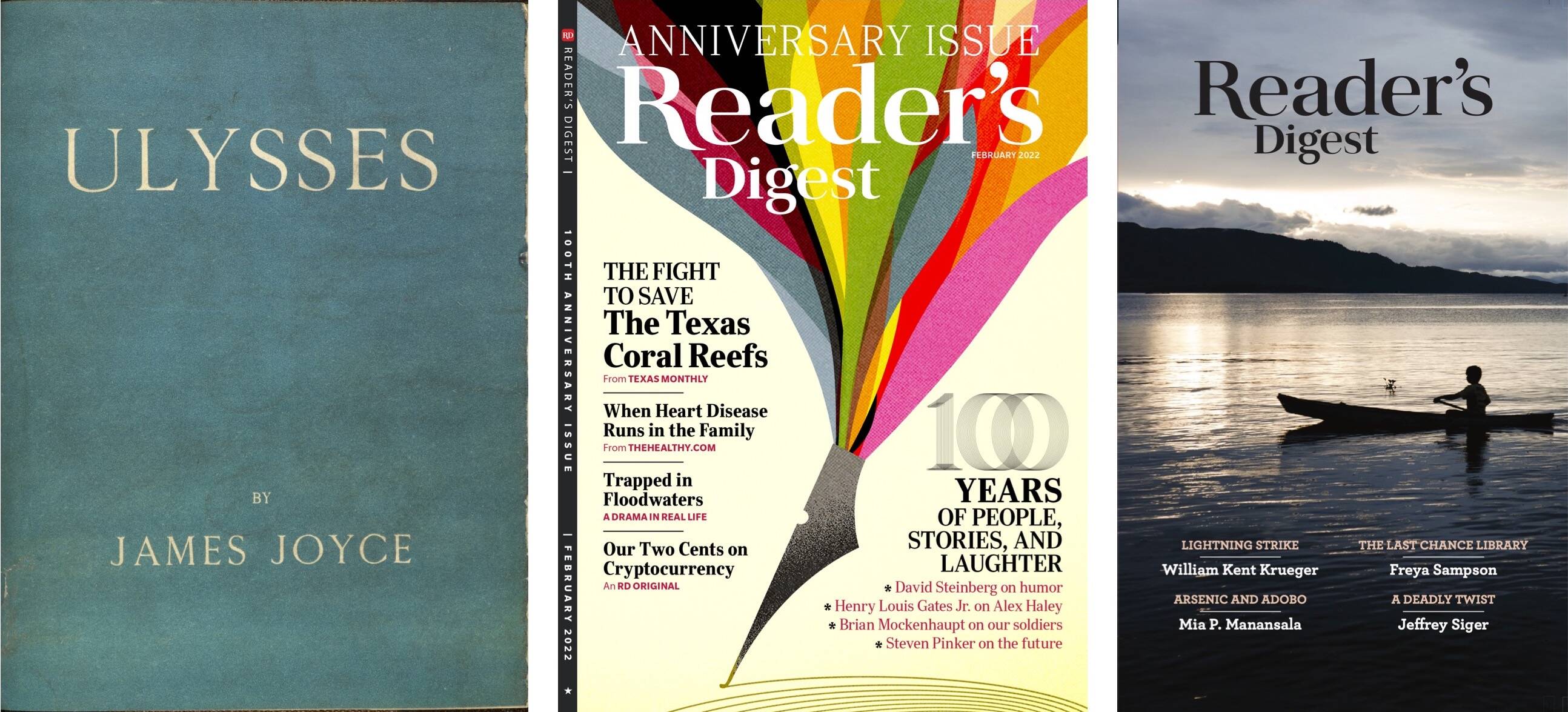

According to data from the American Library Association, the pace of book bannings has accelerated rapidly in the last few months. (FSG; Holt; Pantheon; Algonquin; W.W. Norton) | And then they came for the graphic novels. Last month, the McMinn County, Tenn., school board voted to drop Art Spiegelman's "Maus" from its 8th-grade curriculum on the Holocaust (details). The Pulitzer Prize-winning book, which depicts Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, is about Spiegelman's relationship with his father and his father's ordeal as a prisoner at Auschwitz and Dachau. The minutes from the board meeting demonstrate democracy in action. God help us. One of the members with a particularly screwy sense of how literature functions complained that "Maus" "shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids — Why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff?" (So long, Macbeth!) Another board member, who must have unlimited reserves of patience, explained, "I think the author is portraying that because it is a true story about his father that lived through that." Undaunted, her colleague replied, "This guy that created the artwork used to do the graphics for Playboy . . . and we're letting him do graphics in books for students in elementary school." "It was a decent book until the end," said another board member. "I thought the end was stupid, to be honest with you." Then they voted unanimously "to take the book completely out." Amid all the idiocy perpetuated by America's neo-book-banners, this decision in a small Tennessee town feels particularly appalling. Spiegelman called the school board's action "a red alert." He warned, "It's part of a continuum and just a harbinger of things to come" (interview). If there's any silver lining here, it's that defenders of free expression have spoken up so forcefully and effectively over the last few days. A GoFundMe campaign created by Nirvana Comics Knoxville has already raised more than $100,000 to send a copy of "Maus" to any student in America (story). In response to this controversy, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen published a powerful essay in the New York Times about the crucial role that disturbing, even racist books played in his own adolescence. "Those who seek to ban books are wrong," he writes, "no matter how dangerous books can be." Because irony is the controlling principle of our universe, Tuesday was the release day for the paperback version of Jeanine Cummins's best-selling novel "American Dirt." Its re-emergence is a well-timed reminder of the thorniness of debates about free expression. You may remember that two years ago Flatiron published this melodramatic thriller about a Mexican bookstore owner and her son trying to escape a murderous drug lord. "American Dirt" was marketed as the defining novel of the immigrant experience, but in a spectacular review, Myriam Gurba exposed the story's mawkish cliches and racist stereotypes. Her piece led a rich discussion about cultural appropriation, the Whiteness of American publishing and the barriers that Latinx authors face. But then things went off the rails. Legitimate complaints about "American Dirt" gave way to ad hominem attacks on Cummins. Bookstores were lobbied not to sell the novel. More than 140 prominent writers signed a petition asking Oprah to cancel her book club selection of "American Dirt." And Flatiron had to close down Cummins's author tour, citing "specific threats to booksellers and the author." It wasn't the left's best moment. When yahoos ban a classic work about the Holocaust, it's thrilling to defend the sanctity of free expression. It's a lot more uncomfortable when you know a book is offensive or harmful. But unless we want the survival of every work of literature to be subjected to the whims of power politics, we should keep Nguyen's words in mind: "Those who seek to ban books are wrong no matter how dangerous books can be."  There'll Always Be an England: A Queen Elizabeth II Platinum "Jubbly" commemorative plate (Photo courtesy of Wholesale Clearance UK Ltd.) | The Wordle craze has been particularly lonely for those of us who can't spell. We suffer in silence – like the "b" in "subtle." We live in terror that some perfectly pleasant gathering might suddenly veer into a game of Scrabble. We're ecasperated erratated mad about being repeatedly told, "It's spelled just like it sounds." I still remember being paralyzed on a test in 4th grade trying to sound out the word "of." So I felt a little schadenfreude when I read this week about a Chinese firm that manufactured more than 10,000 commemorative tea cups, mugs and plates to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II's platinum jubilee — the 70th anniversary of her reign on Feb. 6. Due to a spelling error, each one of these 10,000 dishes is printed with the phrase "Platinum Jubbly." Wholesale Clearance UK Ltd. in Dorset is now offering the dishes as potential gag gifts to some daring retailer (details). "Apart from the obvious gimmick factor, there is an abundance of fantastic things you could do with these," the website says. One suggestion: "Take-up plate spinning as a hobby." I'm not sure I could use more than a dozen misspelled commemorative plates, but it would be fun to set them out to subvert my next Bananagrams party.  Counterpoint Press/Catapult; Simon & Schuster; Catapult; background photo by Yves Herman/Reuters. | Families are large, they contain multitudes. Elizabeth Koch is the co-founder and CEO of Catapult, a terrific publisher of fiction and nonfiction. One of Catapult's imprints publishes books by the famed environmental writer Wendell Berry. And this June, Catapult will release "The World As We Knew It," an anthology of essays in which writers such as Lydia Millet and Omar El Akkad "reflect on how climate change has altered their lives, revealing the personal and haunting consequences of this global threat." It turns out that all our lives are being altered by the "haunting consequences of this global threat," in part, because Elizabeth Koch's father, billionaire Charles Koch, has used his dark money to snuff out government action on climate change. You can read about his work in "Kochland," by Christopher Leonard, which our reviewer said offers "compelling, and often scary, reading" (review). Environmental writer and activist Travis Nichols is now calling on Elizabeth to get her family out of the climate-wrecking racket. "While she hasn't explicitly endorsed her family's degradation of American life, she hasn't done anything of consequence to stop it," Nichols writes on Medium. He argues that this coziness must end. What does it mean to buy a copy of "Our Biggest Experiment," Alice Bell's "Epic History of the Climate Crisis," from one of the Kochs? Their "wealth makes the Sacklers seem like a fumbling start-up," Nichols writes, "and yet, the literary community has been reluctant to call out the Kochs in the same way the art community has called out the family of opioid profiteers." Nichols has posted an online petition urging Elizabeth "to use the power of her family's name and network to persuade Joe Manchin, a politician already in the Koch family's pocket, to vote 'yes' on the climate legislation coming up in the Senate." As petitions go, this one seems more impassioned than precise. If Elizabeth is already trying to counter her father's deleterious influence with her life's work, what more can we really ask? And there's something depressing about imploring rich people to bribe old politicians to save the planet for another generation. But maybe that's what America's retail democracy has come to. In any case, Nichols's petition now has more than 2,900 signatures. This week, Andy Hunter announced that he'll step down as the publisher of Catapult on Feb. 18. A spokesperson tells me, "Andy's departure is long planned and mutually supportive, based entirely on his passion for his additional projects and his confidence in the current team at Catapult." Elizabeth Koch did not respond to requests for comment.  New author Dillon Helbig. (Susan Helbig); the first page of Dillon's book. (Ada Community Library) | Tomorrow is Take Your Child to the Library Day. I'm normally dismissive of dubious holidays, but I make an exception for this one and Pi Day (March 14). Librarians in Connecticut launched Take Your Child to the Library Day more than a decade ago to raise awareness "about the importance of the library in the life of a child." Public libraries in most of the 50 states will be participating by offering bookmarks, games, storytimes and author events (more information). When you take your child to the library, you never know what might happen. Have you read the adorable story of the 8-year-old author in Idaho who sneaked his handmade Christmas book onto a shelf at his local library? Before his mother could get the book back, librarians had discovered it, added it to their collection, and now there's a years-long wait list for "The Adventures of Dillon Helbig's Crismis," by Dillon His Self (story). After receiving a crush of publicity around the world, His Self is now reportedly working on a sequel. (Forget the sequel, Dillon — concentrate on a TV adaptation!) In general, librarians would like self-published authors to resist the temptation to smuggle their masterpieces onto library shelves. But Anthony W. Marx, president of the New York Public Library, sends his congratulations to young Dillon. "We couldn't love that story more," Marx tells me. The NYPL offers writing programs that have resulted in original works being placed in circulation. In fact, Marx says, "Dillon's story inspired us so much that we're currently evaluating how we can launch a larger-scale writing project across our whole system."  "Ulysses," by James Joyce, published by Shakespeare and Company, 1922 (British Library); the 100th anniversary issue of Reader's Digest; the latest edition of Reader's Digest Select Editions (Courtesy of Reader's Digest) | "Ulysses," James Joyce's infinitely loquacious novel, turns 100 this week and — in a coincidence so weird it has to be true — so does Reader's Digest. DeWitt and Lila Bell Wallace launched their 25-cent magazine in 1922 as an anthology of articles "in Condensed and Compact Form." Eventually, that would include eye-catching listicles like "9 Telling Signs You're Drinking Too Much Water." If you're of a certain vintage, you grew up in a house lined with Reader's Digest Condensed Books, those gold-stamped hardback volumes that combined the intellectuality of fine literature with the efficiency of a crib note. Launched in 1950, the series sliced the "fat" from bestsellers like Herman Wouk's "The Caine Mutiny," James Michener's "Hawaii" and Harper Lee's "To Kill a Mockingbird." The company sold untold millions of copies, as evidenced by the number of charity drop-off sites that now plead, "Please, no Reader's Digest books." The series, renamed Reader's Digest Select Editions, still publishes seven anthologies a year — each one containing four works of popular fiction, a balance of mystery, romance, thriller and family drama. Incredibly, the staff is now working on its 388th volume. Priced at $24.99, each one sells between 30,000 and 45,000 copies (details). Executive editor Amy Reilly, who's been with Reader's Digest for more than three decades, describes a pruning process of military precision. Each finished anthology must be exactly 576 pages. The included novels are cut down by about 40 percent: dialogue condensed, extraneous characters expunged and unnecessary description excised. "You try to find a storyline and stick to the storyline," Reilly explains. "Two paragraphs of beautiful sunset come down to one line of beautiful sunset." Don't novelists decry such pillaging of their perfectly composed prose? "We have never, literally never had an author contact us and say, 'You ruined my book.'" In the grand tradition of Reader's Digest, naughty words are verboten, and the lights are turned out on erotic scenes. But graphic action usually survives. "We actually have a fair amount of violence because, weirdly, our readers don't mind violence as much as they mind explicit sex," Reilly says. "That is America." In a sense, Reilly and her small staff of editorial surgeons are creating the largest collection of erasure poetry in Western literature. "It always amazes me, even after all these years, with the right kind of book, if you take out stuff, it really still fits together."  Riverhead; Nobel Prize-winner Olga Tokarczuk (Photo by Lukasz Giza/Riverhead); Seven Stories Press | There is no Reader's Digest condensed version of "The Books of Jacob," a 1,000-page epic by Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk. But that's okay. To say this is my favorite novel about an 18th-century Jewish heretic doesn't do it justice. In terms of its scope and ambition, "The Books of Jacob" is beyond anything else I've ever read (rave). Given my fluency in Polish, I could experience this wondrous novel only because it's been so brilliantly translated by Jennifer Croft. Aside from the sheer volume of the work, what's truly amazing is Croft's felicity with the novel's various voices — a vast collage of legends, letters, diary entries, rumors, political attacks and historical records. And through it all, she manages to convey Tokarczuk's delightful irony. To me, imprisoned in my monolingualism, translation is closer to alchemy than chemistry, so I was particularly fascinated by an essay Croft recently published on LitHub. It's a masterclass on the process of drawing sentences from one language into another while preserving their "rhythm, register, and the balance of sanctity or profundity and humor." Croft may have plans for this essay in a collection of her own, but if not, I hope it's included in future editions of "The Books of Jacob." If 1,000 pages feels like too much, try Tokarczuk's 48-page picture book, which is infused with her melancholy humor and surreal imagination. Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, "The Lost Soul" tells the story of a hard-working man who "had left his soul behind him long ago." He goes about his daily activities "as if he were moving across a smooth page in a math exercise book." Finally, alarmed by a crushing sense of loneliness, he consults a doctor who tells him to find a quiet place, sit still and wait for his soul to return. The design of the book has a deceptively antique feel. The haunting illustrations by Joanna Concejo begin with pen-and-ink sketches and finally — spoiler alert! — burst into color. Amid the daily grind of our ceaseless busyness, "The Lost Soul" is a gentle reminder to stop, just stop, and put our mental house back in order.  The Queen Mary 2 will ferry bookworms on a seven-day Literature Festival at Sea in December 2022. (Photo by Jonathan Atkin/Cunard) | Contrary to Emily Dickinson's claim, there is a frigate like a book: Next winter, the Cunard cruise line is offering a seven-day Literature Festival at Sea on the Queen Mary 2. While sailing from New York to Southampton, you can hobnob with such famed novelists as Bernardine Evaristo, Maggie O'Farrell and Alexander McCall Smith, along with classicist Mary Beard and historian Simon Winchester. U.K. Poet Laureate Simon Armitage will be onboard, too — handy, I suppose, should there be a covid outbreak and someone needs memorializing at sea. (Too soon?) The cruise, Dec. 3-10, will include workshops, talks and readings arranged by the Times and the Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival. The super-fancy suites appear to be already sold out, but there are still rooms with ocean balconies, starting at $3,558. If you go, please send me photos! (details)  Harper Perennial Modern Classics; Johnson Publishing, 1971; Library of America | Gwendolyn Brooks started her career with "A Street in Bronzeville," but a few years later her work was traveling the highways of the world. The empathy and precision of her verse revealed the details of ordinary African American life to readers in a strikingly revolutionary way. The first Black writer to win a Pulitzer Prize, Brooks is the subject of a new exhibit at the Morgan Library in New York (online exhibit). "A Poet's Work in Community" displays dozens of manuscripts, broadsides and first editions, including material from Brooks's personal library acquired by the Morgan in 2020. While addressing Brooks's extraordinary contribution to poetry, the new exhibit, which runs through June 5, also highlights her "expansive social and political impact" as a teacher, mentor and activist for racial justice. In a preview presentation, curator Nick Caldwell explained that the show is designed to "explore how community is actually imperative for creative growth and writing." Two decades after winning a Pulitzer for "Annie Allen" (1950), Brooks left the relative security of her storied New York publisher, Harper & Row, and published "Riot" with a young African American publisher in Detroit called Broadside Press. It was a demonstration of her dedication to nurturing other Black authors and a publishing infrastructure capable of promoting them. Soon afterwards, in an interview with Essence magazine, Brooks said, "I've been telling everybody who's black, 'You ought to have a black publisher.'" The Library of America offers "The Essential Gwendolyn Brooks," edited by Elizabeth Alexander (details).  Bloodaxe Books | On Tuesday, "The Kids," a poetry collection by former English teacher Hannah Lowe, was named the Costa Book of the Year. The prize, worth about $40,000, honors "the most enjoyable book" by a writer in the U.K. and Ireland. Several weeks earlier, "The Kids" had been named the Costa Poetry Book of the Year. Lowe's book is a collection of sonnets focused primarily on her life as a teacher in London, but it also looks back to her time as a student and outside the school to dating and grieving. The poems are funny, tender, occasionally inspiring and sometimes achingly sad — which pretty much sums up a career in teaching. The judges said "The Kids" "has a universality to it — in a simple way, because everybody's been to school." Indeed, I want to give copies to half a dozen teachers — starting with my wife and my younger daughter. Something Sweet Winter mornings, I'd buy hot chocolate

and the red-haired green-eyed girl who served me

would smile and sometimes hand me it for free

and I'd drink it down and smoke a cigarette

in the park across from college – something sweet

with something bitter. Before I crossed the track,

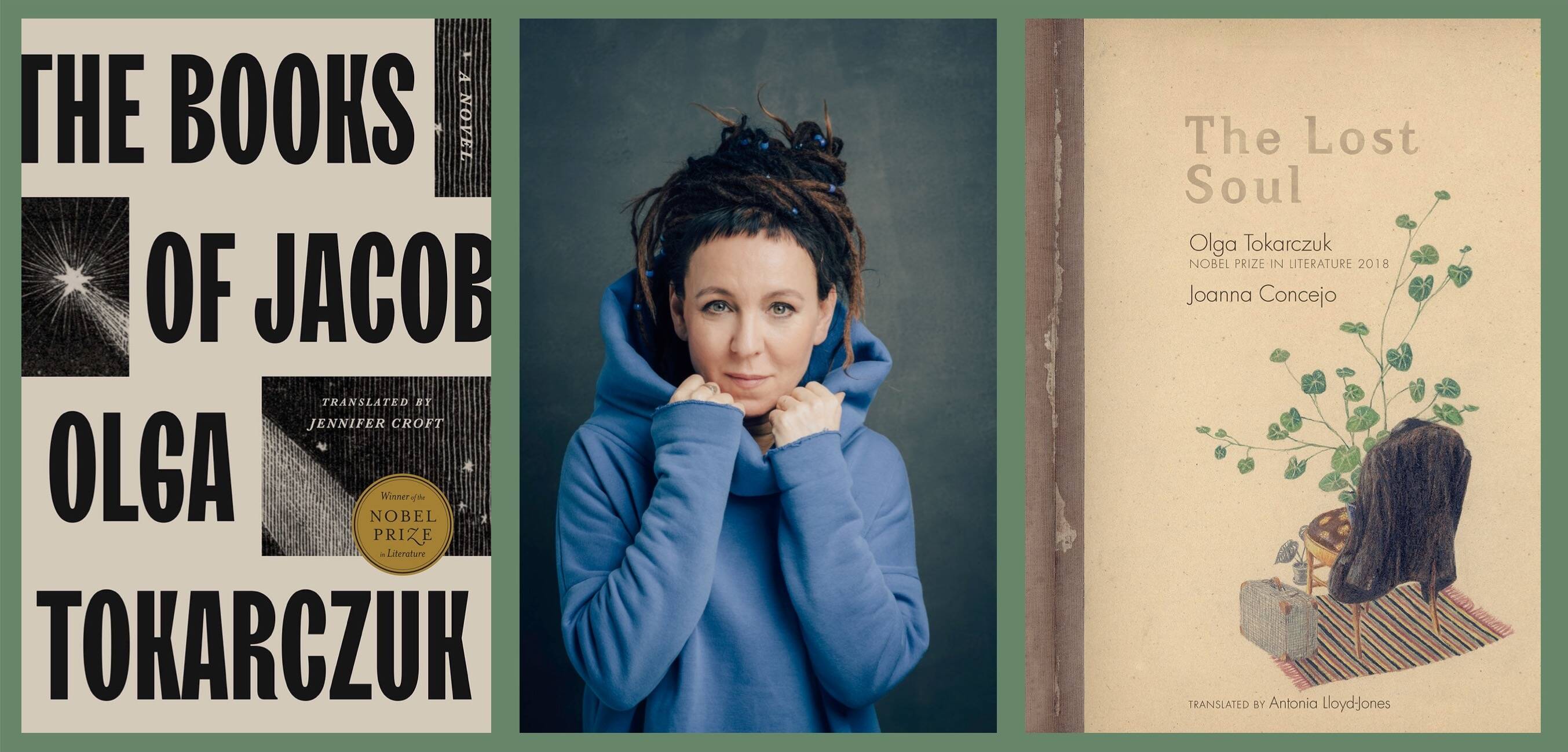

I tucked away my numb heart in an ice-pack

in my pocket, where it felt cold and wet and unforgettable – and went and taught

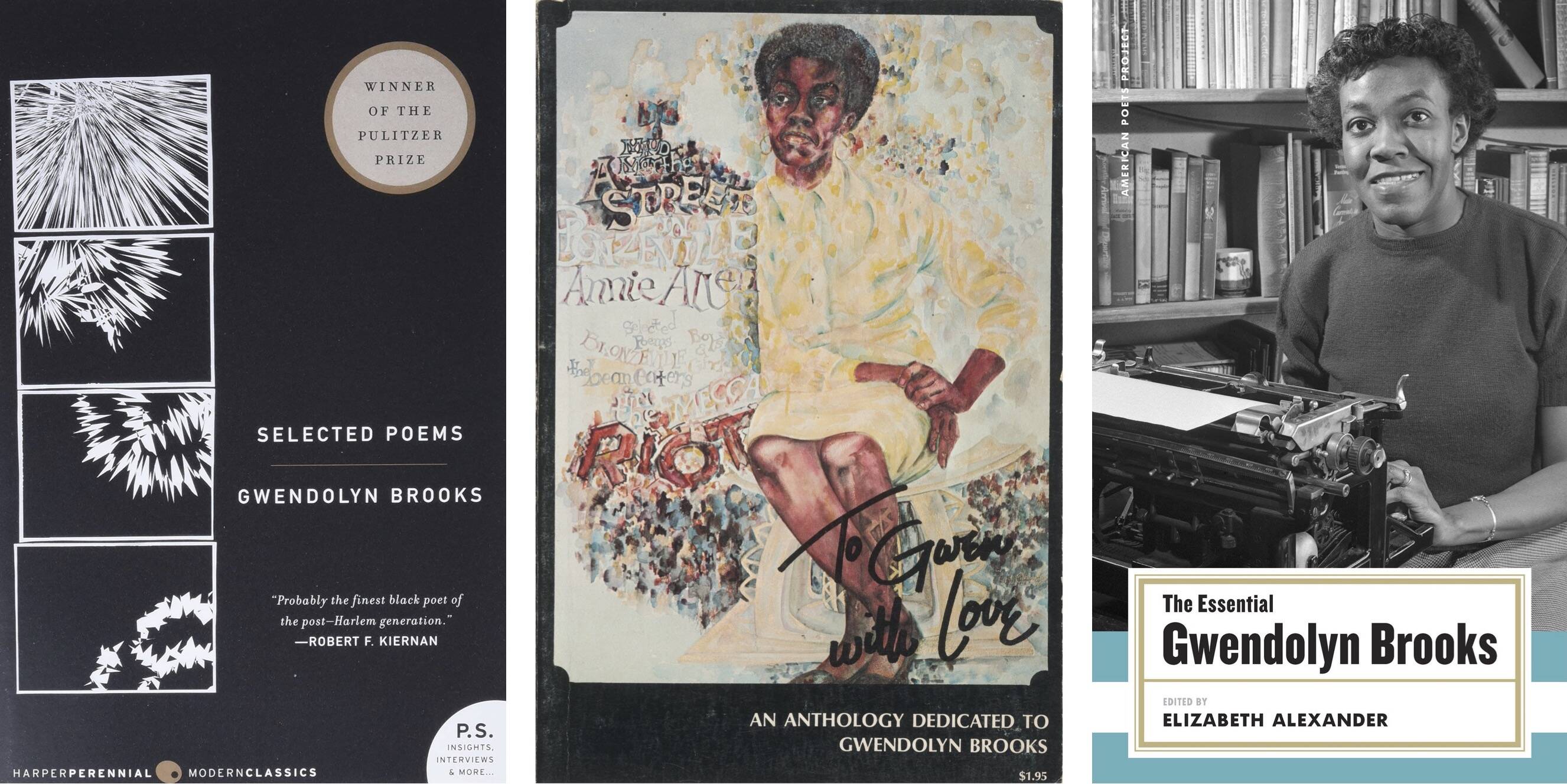

all day, when I didn't care about the theme

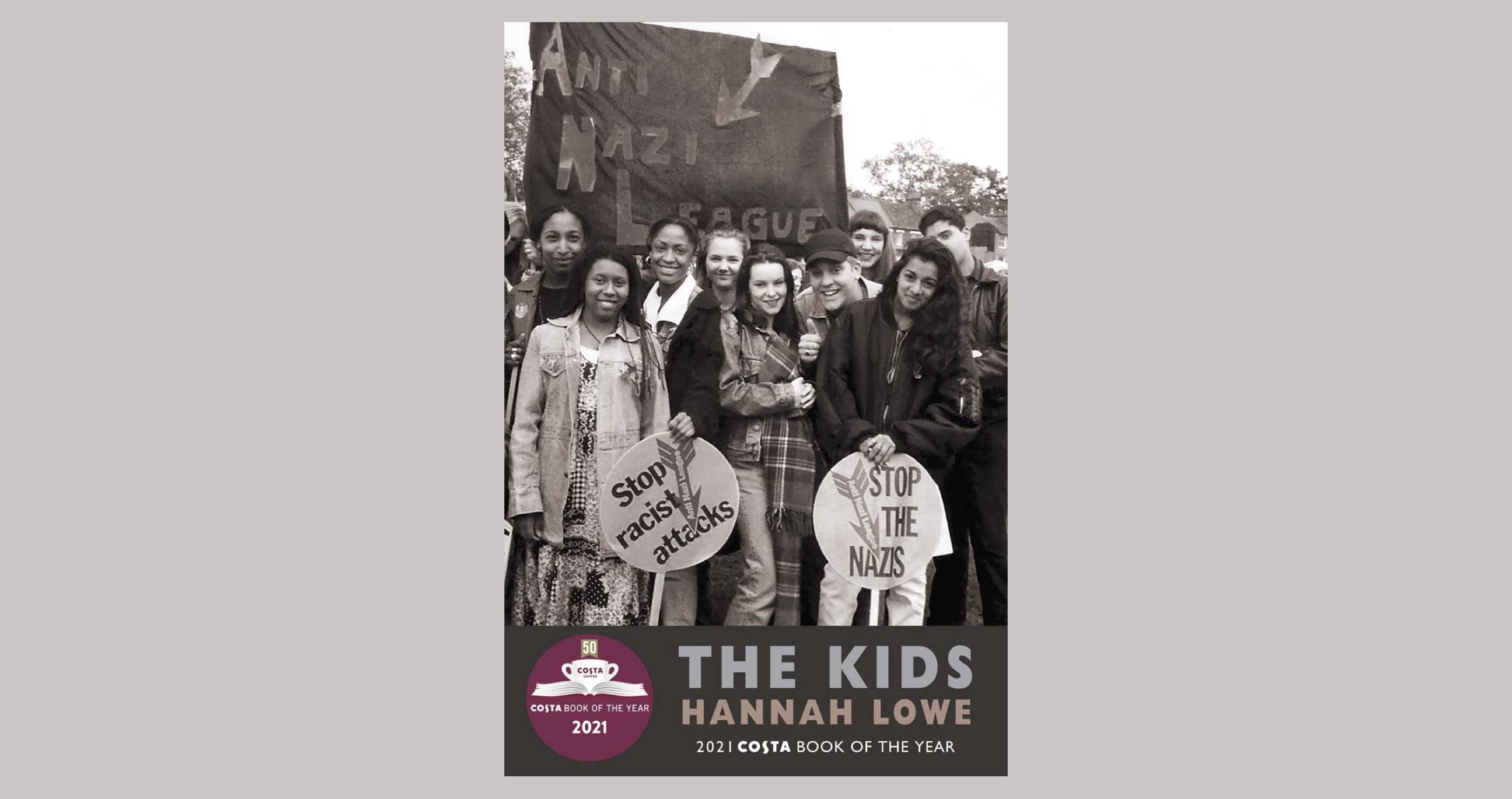

of a poem, the shape of a play. Then marking essays

after class, I'd watch the kids roll out

in their rainbow coats and rucksacks, like streams

of paint – so bright I had to look away. From "The Kids," by Hannah Lowe (Bloodaxe Books, 2021). Reprinted with permission of the publisher.  Vintage; Harper Collins; Hyperion Books for Children | Dawn and I escaped the disastrous snowstorm that walloped most of the country, including my folks in St. Louis. It's actually warmer this week in Washington than it's been for a while, but I've been cooped up so long that now I'm telling you about the weather, so that's kind of a disaster of a different nature. . . . Fortunately, there are books. My younger daughter, who started student teaching this week in Brooklyn, is reading Ernesto Quiñonez's "Taína" to get ready to study it with her class. I'm reading Tessa Hadley's "Free Love," which I'll tell you about next week. And my wife, who teaches 11th grade English, is reading 10 short stories for high school students suggested by Nikki DeMarco on Book Riot (full list). We're looking forward to a Zoom dinner with some friends Sunday night, which is a sentence I couldn't have fathomed two years ago. Meanwhile, if you have any questions or comments about our book coverage, write to me at ron.charles@washpost.com. You can read last week's issue here. And if you know someone who might enjoy this newsletter, please forward it and mention that it's free! To subscribe, click here.

Interested in advertising in our bookish newsletter? Contact Michael King at michael.king@washpost.com. |