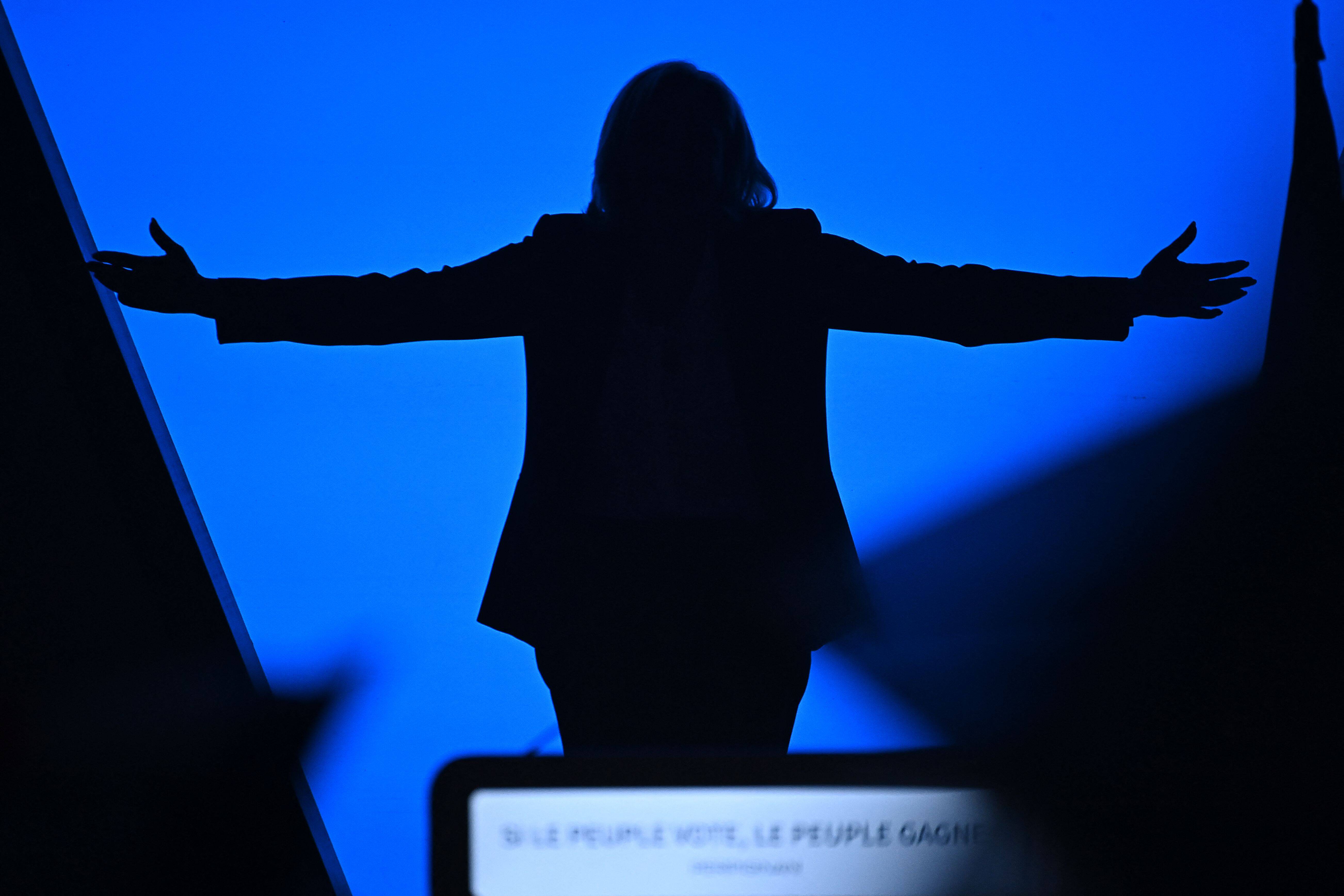

French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen is seen in silhouette as she holds a campaign rally in Perpignan, France, on April 7. (Lionel Bonaventure/AFP/Getty Images) | More than a month ago, French President Emmanuel Macron's reelection seemed a certainty. He comfortably led in the polls ahead of rivals to the left and right. The French public watched in shock as Russian forces poured into Ukraine. Macron's main challenger, far-right perennial Marine Le Pen, was hobbled by her historic rapport with the regime of Russian President Vladimir Putin and stated admiration for his approach to governance. A second-round runoff against either Le Pen or far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon, another figure with a dim view of NATO and a perceived friendliness toward Putin, was bound to be a formality. Macron, who came to power in 2017 as a radical centrist eager to shake up French politics and play a more assertive role on the European stage, embraced the part of continental statesman. "People always rally around a wartime leader," Nicholas Dungan, a senior fellow of the Atlantic Council, told my colleague Rick Noack. "The leadership by Macron is completely consistent with the image the French have of what their country should be doing: It's a global power, it needs to be listened to, it should be aiming for peace." As Sunday's first-round vote nears, though, Macron has reason to sweat. He will likely finish at the top of the pack, but polls now show a statistical toss-up between him and Le Pen should they face each other in the second round on April 24. "It's one minute to midnight," former prime minister Manuel Valls wrote in a column in French weekly Le Journal du Dimanche. "Marine Le Pen could be elected president of the republic." Le Pen has closed the gap on Macron no matter the bad odor of her and her party's Russophilia — her supporters had even circulated a campaign leaflet showing her shaking Putin's hand — and the frequent broadsides from Macron's camp. French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said Thursday that, in a France led by Le Pen, "there would be less sovereignty because we would be allies of Russia, of Vladimir Putin." The reality is Le Pen has surged on the back of voter concerns that have little to do with the geopolitics of ending the war in Ukraine. "Polls show that a majority of the French worry that the cost of living has increased under Macron's presidency, even as the economy overall has weathered the coronavirus pandemic and other crises," my colleagues explained. "The war in Ukraine has prompted growing concerns over rising inflation, surging energy prices and insufficient pensions." Le Pen, who lost in a landslide to Macron in 2017, has tried to detoxify her and her party's image as one steeped in neo-fascist resentments, racism and anti-Semitism. She was aided by the maverick campaign of ultranationalist gadfly Eric Zemmour, whose snarling anti-immigrant, anti-establishment rhetoric has made Le Pen — a far-right mainstay for years — look comparatively moderate. And her campaign has waved the banner of economic populism as much as it also tries to harness far-right cultural anxieties. Le Pen condemned the invasion of Ukraine as a violation of international law and has welcomed Ukrainian refugees. "She was able to change her brand image," David Dubois, professor of digital marketing at Insead, a leading business school, told the Financial Times. "She's really made an effort to change her discourse from immigration to rising prices and how to increase the purchasing power of French people." Contrast that with Macron, who has throughout his five years in power been viewed as an aloof elitist — a "Jupiterian" president, as the French put it, ensconced in his Olympian abode. The former investment banker is attacked both by Le Pen and his critics to the left as an effete figure ruling for the rich, disconnected from the concerns of ordinary French workers. "Le Pen did a proximity campaign, visiting a lot of small towns and villages. Her trips were not very much covered by national press but had a big echo in local media," Mathieu Gallard, research director at polling firm Ipsos, told Politico. "She gave an impression of proximity, which is very important for French voters." In an interview with the Spectator, a right-leaning British publication, Le Pen cast Macron as an agent of global capital. "The policies I want to implement are not meant for the stock markets, which will be a change from Emmanuel Macron," she said. "It's not the markets that create jobs, it's not international finance." She claimed Macron's objective is "to encourage nomadism, the permanent movement of uprooted people from one continent to another, to make them interchangeable and, in essence, to render them anonymous." (No matter that, on questions of national identity and religious freedoms, Macron's government has pivoted sharply to the right.) When asked what leaders she admired on the world stage, she named three right-wing nationalists: India's Narendra Modi, Britain's Boris Johnson and Putin. "I have respect for Vladimir Putin because he defends the interests of Russia," she said. Such rhetoric suggests that her rebranding is purely cosmetic. That's Macron's contention, anyway. "The fundamentals of the far right are always the same: attacks on and rejection of the Republic, a base of antisemitism — if not overt, at least cultivated — very clear xenophobia and an ultraconservative drive," he said in an interview with Le Figaro, a French daily. |

The scope of barbarity  Police officers work in the investigation process following the killing of civilians in Bucha, Ukraine on April 6. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post) | BUCHA, Ukraine — The name of this city is already synonymous with the month-long carnage that Russian soldiers perpetrated here. But the scale of the killings and the depravity with which they were committed are only just becoming apparent as police, local officials and regular citizens start the grim task of clearing Bucha of the hundreds of corpses decomposing on streets and in parks, apartment buildings and other locations. As a team from the district prosecutor's office moved slowly through Bucha on Wednesday, investigators uncovered evidence of torture before death, beheading and dismemberment, and the intentional burning of corpses. Some of the cruelest violence took place at a glass factory on the edge of town. On the gravel near a loading dock lay the body of Dmytro Chaplyhin, 21, whose abdomen was bruised black and blue, his hands marked with what looked like cigarette burns. He ultimately was killed by a gunshot to the chest, concluded team leader Ruslan Kravchenko. His body then was turned into a weapon, tied to a tripwire connected to a mine. "Everyday we get about 10 to 20 calls for bodies like this," Kravchenko said. The group worked quickly but gently, crouching over Chaplyhin's body and noting minute details on clipboards. On a dirt path behind it was an even more grotesque scene: two victims, their bodies bloating. One man's head had been cleanly sliced off, burned and left by his splayed feet. Investigators found no identification cards on either of the individuals, whose gloves were still in coat pockets despite the frigid cold. The team called several men from the surrounding area to help with identification. A man who gave his name as Alexei said both were security guards at the factory. He recounted how Russians had come to his house three times while drunk and spoke about committing sadistic acts against Ukrainians. Farther down the path, another corpse. Empty bottles of vodka lay in the grass beside it. It appeared that someone had tried but failed to behead this man, too. The factory is just one fragment of the bloodied city. In Bucha's cemetery, 58 body bags were lined up on Wednesday. All but one contained bodies of people who had been summarily executed or tortured to death, according to Vitaly Chayka, an employee who has been processing the dead. — Max Bearak and Louisa Loveluck Read more: In Bucha, the scope of Russian barbarity is coming into focus |