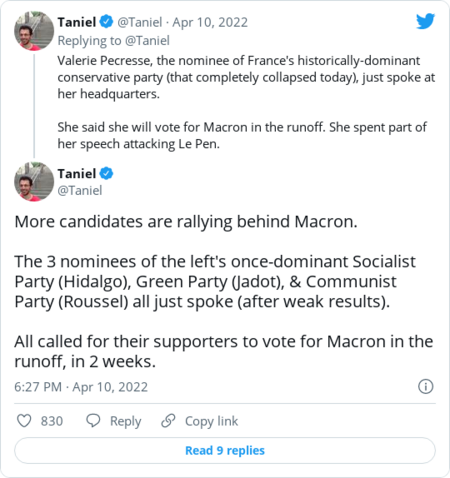

French President Emmanuel Macron attends a campaign rally at Paris La Defense Arena in Nanterre, France, on April 2. (Sarah Meyssonnier/Reuters) | Charles de Gaulle, the towering French leader who ushered in the country's Fifth Republic, believed in a strong presidency anchoring a strong, stable state. The constitution that he and his allies implemented provided for direct universal suffrage elections for the presidency, organized over two rounds. By doing so, executive power in France could be insulated from the vagaries of parliamentary and party politics. The second round runoff, moreover, would likely help protect the republic from extremist challengers, who in theory could never command a majority of votes in a two-person contest. That logic may still hold more than six decades later as French voters await the April 24 second round runoff between President Emmanuel Macron and far-right candidate Marine Le Pen. But it may not. Le Pen — who finished, as expected, second in first-round round voting Sunday, three points behind Macron — will likely not in two weeks face the same landslide defeat that Macron scored over her five years ago. Macron had emerged then as a young maverick centrist who campaigned on a platform of "neither left nor right." In 2017, a big-tent coalition of voters across the political spectrum united to give him a resounding runoff victory over Le Pen, the scion of a movement once rooted in neofascism and anti-democratic violence. Polls now suggest a far tighter contest, with many on the French right and potentially even some voters from the far-left casting a ballot for Le Pen. Abstentions from a growing pool of people disenchanted with their options and tired of Macron may also boost Le Pen's chances. Macron, far from an outsider reinvigorating the French state, appears to many of his opponents as the aloof agent of a wealthy elite establishment and custodian of a fragile status quo in need of reform. Le Pen worked hard to detoxify her and her party's image, casting herself as an empathetic economic populist. She was also somewhat aided by a rival far-right bid from ultranationalist gadfly Eric Zemmour, whose incendiary rhetoric served to make her look all the more moderate. "Le Pen largely avoided emphasizing her most controversial proposals and instead focused on echoing popular concerns about the economy and rising inflation," explained my colleague Rick Noack. "But in their substance, many of Le Pen's positions are as radical as they were five years ago. This past week, she vowed to issue fines to Muslims who wear headscarves in public." "For many French people, the Le Pen name is no longer viewed with disdain," wrote the Guardian's Kim Willsher, on the trail with the far-right candidate. Now, she added, "Macron will face the biggest political fight of his career to keep her out of the Élysée Palace." Le Pen's seeming rehabilitation is also thanks to Macron's own political trajectory. While the country's traditional mainstream factions — the center-left Socialists and center-right Republicans (standard bearers of de Gaulle's political legacy) — remain relevant in local and municipal votes, they have been humbled on the national stage, losing most of their voters to Macron and his movement. In the presidential vote, they were wiped out, pooling less than 7 percent of the vote, collectively. "A complete reconfiguration of French politics is about to take place," said Tara Varma, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, in an email. "It started in 2017 but will now be achieved." Meanwhile, more than half the French electorate opted for candidates on the anti-establishment extremes, including Le Pen, Zemmour and far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who finished just short of Le Pen. "What is happening is that the moderate left and right are disappearing," said Pierre Mathiot, the director of Sciences Po Lille, to my colleagues. "Macron is in the process of crushing the center of politics — but the more he crushes it, the more he gives room to the radical wings." Other analysts argue that Macron is, himself, a center-right politician. He "has systematically adopted [the mainstream right's] core positions, including retirement at 65, work requirements for welfare beneficiaries, and a reduction in the inheritance tax. This amounts to a full-scale takeover of the French center right," wrote Daniel Cohen, president of the Board of Directors of the Paris School of Economics. "If Macron is re-elected, he will preside over a formidable big-tent party, and the Republicans will be left with crumbs, squeezed between a resurgent far right and a governing party that is intent on devouring them." Part of what's in play follows trends familiar elsewhere in Western European politics — specifically, the weakening of traditional mainstream parties in favor of a more complicated, fragmented political scene. But in France, unlike Germany, environmental politics championed by the center left took a back seat to culture warring over immigration and national identity. By the end of his term, Macron had pivoted sharply right, unfurling legislation against "Islamist separatism" in French society, while his allies inveighed against "Islamo-leftism" in universities.  | | | The cultural anxieties coursing through the election campaign won't be easy to reconcile. "I want to be optimistic," Shahin Vallée, a former Macron adviser now at the German Council on Foreign Relations, told the New Statesman. "But it is a long-run optimism — that we can get over these tensions and accept this multi-faith and multi-cultural society, which means accepting a different definition of universalism from the one we have now." For the time being, though, the French left appears demotivated and divided, while the French president may continue fighting Le Pen on her terrain. "Macron is playing a dangerous game," wrote Didier Fassin, director of studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris. "By absorbing his opponents' views into his own platform, he risks bringing about a political landscape hazardously skewed to the right." Far from being a "rampart" against the far right, Fassin warned, Macron may end up "offering a bridge" to them. |

Weapons wrangling  Ukrainian members of the Azov Battalion as they practice shooting live bullets at a training site in Kyiv on March 24. (Heidi Levine for The Washington Post) | Ukrainian officials are clear on what they want from the United States and Europe: weapons. Big, heavy weapons. Not helmets. Tanks. They say they need these weapons now, not later. And a lot of them. The message has been broadly the same from the start of Russia's invasion, when Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky reportedly said "I need ammunition, not a ride," to this past week, when Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba told NATO leaders in Brussels that he had a threefold agenda: "weapons, weapons and weapons." But in the United States and Europe, the discussions over what types of weapons to send are far different from what they were just six weeks ago. This is a pivotal moment of the war, and as the battlefield shifts, the sorts of weapons Ukrainian forces need are changing, too. There is no longer a fear that the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, could fall within days. Russian forces are repositioning for a fight over eastern Ukraine — what many predict will be full-scale confrontation on flat, open, rural terrain, between infantry, armor and artillery, in the kind of engagements not seen in generations. On Saturday, Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson made a surprise visit to Kyiv to meet with Zelensky. His main message was about weapons: that Britain would supply 120 more armored vehicles, in addition to anti-ship missile systems to support Ukraine in the Black Sea. This next phase of war in Ukraine could be "protracted" — "measured in months or longer," national security adviser Jake Sullivan warned. It could look like something from World War II, with two large armies facing off, Kuleba told NATO foreign ministers. In the early days of fighting, NATO countries worried that the weaponry they gave to Ukraine might be quickly captured by superior Russian forces, or that Ukrainian troops did not have the time to train to use new equipment effectively, or that sending offensive weapons would escalate the conflict and enrage Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was rattling his nuclear sword. Weapons are easier to give than to take back. But as the war has gone on, those concerns have begun to recede. Now, some NATO countries are preparing to supply Ukraine with more lethal, sophisticated, long-range and heavily armored weapons. — William Booth, Emily Rauhala and Michael Birnbaum Read more: What weapons to send to Ukraine? How debate shifted from helmets to tanks. |