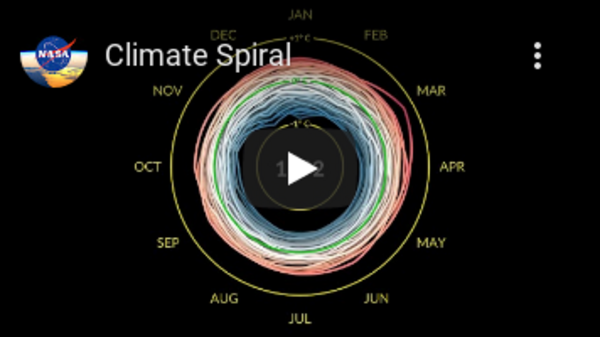

| | | | Developments from Ukraine • A month has passed since blasts woke Ukrainians at 5:07 a.m. on Feb. 24. The sounds of explosions still scare but don't surprise. Each day since has brought the wail of air-raid sirens, the screech of breaking glass and numbingly frequent moments of silence for the dead. My colleagues provide a snapshot of Ukraine one month into the war. • Roughly 7,000 to 15,000 Russian troops have been killed in four weeks of fighting, a senior NATO military official said. The official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity under NATO ground rules, said the estimate was based on several factors, including information from Ukrainian officials, what the Russian side has released and open sources. • The United States and its European allies reinforced their tough stand against Russia, sharply warning Moscow against using chemical weapons in Ukraine and announcing new sanctions on Russians. President Biden voiced support for expelling Russia from the Group of 20, and also announced plans for the U.S. to accept 100,000 Ukrainian refugees. • The FBI is trying a novel strategy to recruit Russian-speaking individuals upset about the country's invasion of Ukraine: aiming social media ads at cellphones located inside or just outside the Russian Embassy in Washington. The targeted ads are designed to capitalize on dissatisfaction within Russian diplomatic or spy services, an event that counterintelligence experts call a huge opportunity for the U.S. intelligence community to recruit new sources. | | |  An activist member of opposition party Justice First holds a placard showing the face of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro during a protest against the Russian invasion in Ukraine, in Caracas, Venezuela, on March 4. (Federico Parra/AFP/Getty Images) | Confronting a conflagration in Eastern Europe after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Biden administration has redoubled efforts to put out fires elsewhere — seeking to accelerate a nuclear deal with Iran and ease strained relations with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. But Washington's most receptive rapprochement is unfolding in fits and starts closer to home, in a country the Kremlin has sought to turn into its most distant satellite: authoritarian Venezuela. Senior U.S. officials this month held their highest-level meeting with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in years. The session with Maduro, his influential first lady Cilia Flores and a small number of other top lieutenants was described by several people familiar with the encounter as "cordial," and successful in establishing personal rapport. Despite White House efforts to downplay the meeting after a backlash by Maduro critics — particularly the powerful Democratic senator from New Jersey, Robert Menendez — lines of communication between Caracas and Washington remain "open," these people say. They spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive information. There had been discussion of a follow-up meeting, but the administration appears to be weighing the pros and cons of further direct talks. Even considering such a dialogue was previously unthinkable. The Trump administration had courted North Korea's ruthless leader Kim Jong Un. In contrast, it launched a "maximum pressure" campaign against Maduro — a figure widely reviled by the Venezuelan and Cuban diaspora in the United States. Trump's hard line was a gift to Florida Republicans, who made substantial gains in exile-heavy Miami-Dade County and won Florida, if not the 2020 election. A U.S. ban on Venezuelan crude devastated the OPEC nation's already-troubled oil industry. The United States shuttered its embassy in Caracas. Direct flights between the United States and Venezuela were halted. The U.S. Justice Department indicted Maduro on narco-trafficking charges. The Trump administration backed opposition figure Juan Guaidó as the country's rightful leader and predicted Maduro's imminent fall. None of it worked. Support for Guaidó would crumble at home. Maduro's opposition, always fractured, has descended into infighting. Some observers give Guaido's interim government to the end of the year until it unravels. Maduro's grip on power, meanwhile, has only strengthened — along with Russia's footprint in Venezuela. A possible shift in policy under Biden never materialized, as observers viewed the administration as either fatally indecisive or exceedingly cautious — eager not to alienate Menendez as well as a key niche of Florida voters. Enter Moscow's invasion of Ukraine, the surge in global oil prices and the unmasking of Russian President Vladimir Putin as an existential threat. The visit this month from a U.S. delegation that included Juan Gonzalez, the National Security Council director for the Western Hemisphere, and U.S. Ambassador to Venezuela James Story yielded the release of two American citizens, including a former executive of Citgo, once part of Venezuela's state oil company. Freedom for a third American — a former marine who Venezuelan officials insist is a covert American operative — came close to happening but didn't. In Washington, the narrative of the visit has largely centered on oil — the potential of easing the U.S. ban, and creative deals that would allow Western companies, including California-based Chevron, back in. But Venezuela's oil industry is in dire straits — with poor infrastructure that would take billions of dollars of investment to improve, along with months to significantly increase production. A deal could have a psychological impact on markets. But even the most generous estimates suggest Caracas could only ramp up to about 15 percent of Saudi Arabia's current output in the medium-term. In short, Venezuela is unlikely to be a massive factor in lowering gas prices at American pumps. But the American rapprochement is also about geopolitics, and countering the already-deep Russian-Venezuelan alliance. That alliance is based on oil deals. But it comes with military cooperation that should worry Washington. Between 2006 and 2013, when Maduro's predecessor Hugo Chávez died of cancer, Venezuela bought nearly $4 billion in Russian military equipment. In late 2018, two nuclear-capable, long-range Russian Tu-160 bombers arrived under sunny skies at Maiquetia International Airport outside Caracas, met by senior Venezuelan military officers who saluted and shook hands with the pilots. The Russians later took part in joint exercises. A year later, Moscow dispatched dozens of Russian military personnel and tons of equipment to Venezuela. The administration has publicly laughed off post-invasion suggestions by Moscow of ramped up military cooperation with Caracas. The Russian military is now so stretched in Ukraine that a replay of the 1962 Cuban missile crisis in Venezuela appears far-fetched. But that doesn't mean the United States can't keep Moscow second-guessing about its web of alliances, particularly in Latin America. Maduro's government was unnerved by Russia's invasion of Ukraine, fearing Washington could one day use the "not-in-my-backyard" argument against Caracas. After the U.S. delegation's visit this month, Moscow was sufficiently alarmed to summon Maduro's No. 2, Delcy Rodriguez, for a meeting in Turkey to review their strategic alliance. The Venezuelan government, according to two people familiar with its thinking, is interested in continuing the direct talks. But critics say the administration has mismanaged its attempted opening — failing to brief key players on Venezuela policy and suddenly backtracking when the trip sparked an easily anticipated backlash. Menendez, whose key vote the administration will want on any nuclear deal with Iran, was livid over being blindsided. Guaidó, equally caught off guard, was sufficiently furious as to fire off a personal letter to President Biden. The problem may be partly one of sequencing and forum. Menendez co-sponsored the 2019 Verdad Act that enshrined the search for a "negotiated solution to Venezuela's crisis" into U.S. law. He may not necessarily be opposed to easing U.S. sanctions if Maduro agrees to concrete steps toward restoring democracy, though he is likely to seek movement through a currently stalled dialogue in Mexico with Maduro's opposition. His biggest beef, echoed by other critics, is over the chance that Maduro could be rewarded with oil deals just because his ally Putin is wreaking havoc in Ukraine. Restarting the Mexico talks was a key request by the U.S. delegation that visited Caracas. But the opposition remains so fractured that progress without direct U.S. talks would be slow. Maduro, meanwhile, has cracked a U.S.-backed isolation campaign, already earning a softening stance from the European Union. With leftist presidential candidates who are signaling an even gentler stance toward Caracas leading in the polls in Colombia and Brazil, it may be only a matter of time before Maduro shatters it. The question for the administration is whether it's willing to close a door it just opened, and whether that gives Putin room to expand his reach in a country that sits three hours by plane off the coast of Florida. | | | Top of The Post | By Sarah Kaplan, Naema Ahmed, Anna Phillips, Andrew Van Dam and John Muyskens ● Read more » | | | | By Michelle Ye Hee Lee, Min Joo Kim and Julia Mio Inuma ● Read more » | | | | | | Viewpoints | | | The war, from our photojournalists' eyes One month into Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the loss and destruction is hard to put into words. Washington Post photographers have been on the ground from the very beginning — here's some of their most powerful work. Michael Robinson Chavez, in Novotroitske, Ukraine In early February, two of my colleagues and I joined a group of Ukrainian special forces on the eastern front of the "Gray Zone," a border between the area controlled by Ukraine and the area held by Russian-backed separatists. It was cold, wet and muddy. The soldiers toiled in the mud digging out bunkers and trenches. We stayed at their barracks in the half-abandoned town of Novotroitske. We slept in their barracks and ate at the mess hall, which was adorned with children's well-wishes and drawings. My bunk was festooned with Christmas lights, as was my neighbor Vanya's. Vanya is a kind soul who openly talked about post-traumatic stress disorder and all the fighting he went through in the years since 2014. For the first couple of weeks of the Russian invasion, we had no idea what had become of him or his fellow soldiers. Fortunately, he surfaced and got word to us that he was alive and okay. Others in the group, including Oleksander, the commander, had been injured. Still, others were killed. I hope that I can see Vanya again and laugh about the accommodations we shared. Heidi Levine, in Kyiv, Ukraine Within the very first days of the war, I witnessed and documented the largest exodus of refugees fleeing to bordering countries for safety since World War II. It felt as though people were running from a tidal wave crashing down on their lives, most leaving their sons, fathers, husbands and even grandfathers behind to fight for their country. In the city of Irpin, people carried their children, their elderly, their disabled and whatever belongings they could take with them. Some often collapsed from the journey against the sounds of war and crackle of gunfire. Even their pets showed fear in their eyes as their owners tried to keep their balance while crossing the shaking planks of wood over the icy Irpin river. During one snowstorm, the images I made of an elderly woman covered in snow as her family struggled to push her in a supermarket cart made me wish to caption my photos with a single sentence: "What if this was your grandmother?" Salwan Georges, in Kharkiv and Odessa, Ukraine It was 5 a.m. on Feb. 24 when ground-shattering booms woke Kharkiv. At that instant, I knew Russia's invasion of Ukraine had begun. I threw on my helmet and flak jacket, both with the word PRESS on them, and headed to the streets. Within hours, the platform of an underground subway station became a refuge for women and children. Family members embraced as the sound of explosions intensified above them. At a territorial defense center nearby, many civilians lined up to join in defense of their country. They filled the backs of trucks and were sent to the front lines to fight. In Odessa, as thousands boarded trains to leave the country for Poland, I met Georgiy Keburia as he kissed his wife, Maya, goodbye through the train's window, wiping away the tears. On International Women's Day, I met Katya as she held a rifle, learning how to use it to defend her country. In Mykolaiv, I met Diana as she spent her fifth birthday in a bomb shelter surrounded by her family. Just a few blocks away, at the city morgue in Mykolaiv, other families came to identify their sons killed on the battlefield. I will never forget walking through rooms filled with the corpses. People of all ages who gave up their life defending Ukraine. Kasia Strek, in Poland and Lviv, Ukraine One night after the curfew fell on Lviv, I saw a family running through the streets. A grandmother with her daughter and her granddaughter, who was tightly clinching a doll to her chest. The terrified look on the little girl's face caught my eye. There it was, three generations of women fleeing the war, while the men in their lives stayed behind to fight. In the last few weeks we met a lot of women and their children. All of them trying to stay strong. I met women already at the Polish side of the border who did not know what they would do next, as well as women deciding to remain in Lviv or in the mountains to stay closer to their partners, brothers and fathers. Women who decided to abandon their previous lives and work to protect Ukraine in any way they could. During all these meetings, we mainly talked in a mixture of Polish and Ukrainian languages. This mutual understanding made me feel personally closer to all of them. It made me realize very strongly how similar we are and how, because of the border that separates our two countries, we now live in very different realities. Wojciech Grzedzinski, in Kharkiv, Bela Tserkva and Lviv, Ukraine This war hurts me because it's just around the corner. It's on my country's borders [Poland]. I have been there several times in the past years, working and having a good time. I have Ukrainian friends, and their life collapsed in the blinks of an eye. I'm not surprised how courageous they fight. I'm not surprised how well organized they are and how helpful they are to one another. Ukrainians are giving everyone an example of what the word "humanity" means. It's an amazing lesson we all can use. I am speechless with the brutality with which civilians are attacked. They became the main target in this war. Shelled with rockets and artillery. Living in dark basements with no water, electricity, or heating and still hoping for peace. Read more: In photos — he war in Ukraine one month on | | | Afterword  A visualization from NASA's climate change team | | | | |